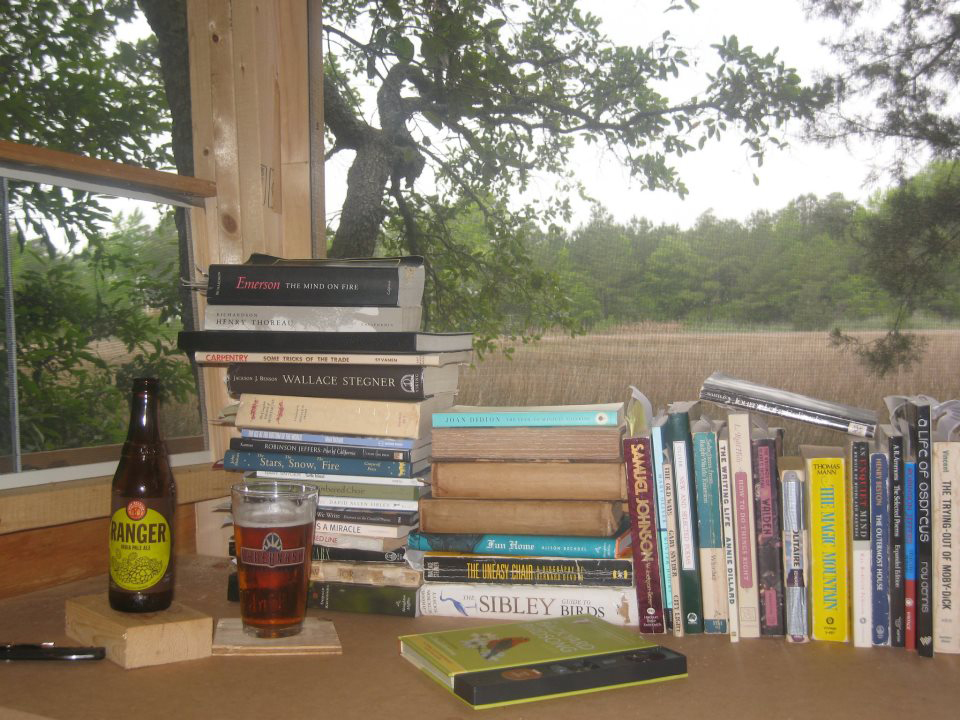

THE WRITER and environmental provocateur David Gessner, is lounging in his writing shack out back of his North Carolina house, a non-smartphone to his ear, a Ranger pale ale in his belly, and another in his hand.

We’re chatting about the latest book, All The Wild That Remains, an encomium to two giants of American literature, Ed Abbey and Wallace Stegner. The shack’s windows face an expansive marshland cut by the turbid waters of Hewletts Creek, a slow-moving meander that flows east to the Atlantic by way of the Intercoastal Waterway, through which Gessner occasionally kayaks. I imagine his flip-flopped feet propped up on his writing desk amidst a scrum of dog-eared books and that morning’s writing as the sun sets behind the ornate cupolas of the University of North Carolina Wilmington ten or so miles to the west, where he teaches literature and creative writing during the fat part of most days.

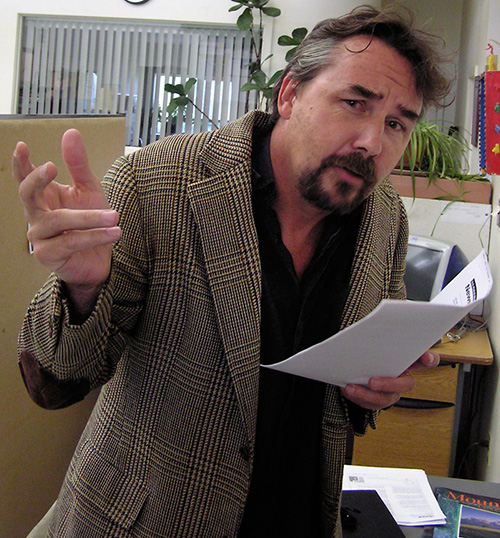

When I last saw him in Reno, Nevada, he had forgotten to pack a belt, so his trousers were secured with a hank of clothesline, Jethro Bodine style, and he read huskily from All The Wild That Remains to a packed lecture hall at the local university. He also paid a visit to ecocritic Michael Branch’s seminar in environmental literature and humor, where I was lurking as a student, and he discussed the state of the nature writing art, the new book, and his eight others, including the genre-bending, anti-Thoreauvian Sick of Nature.

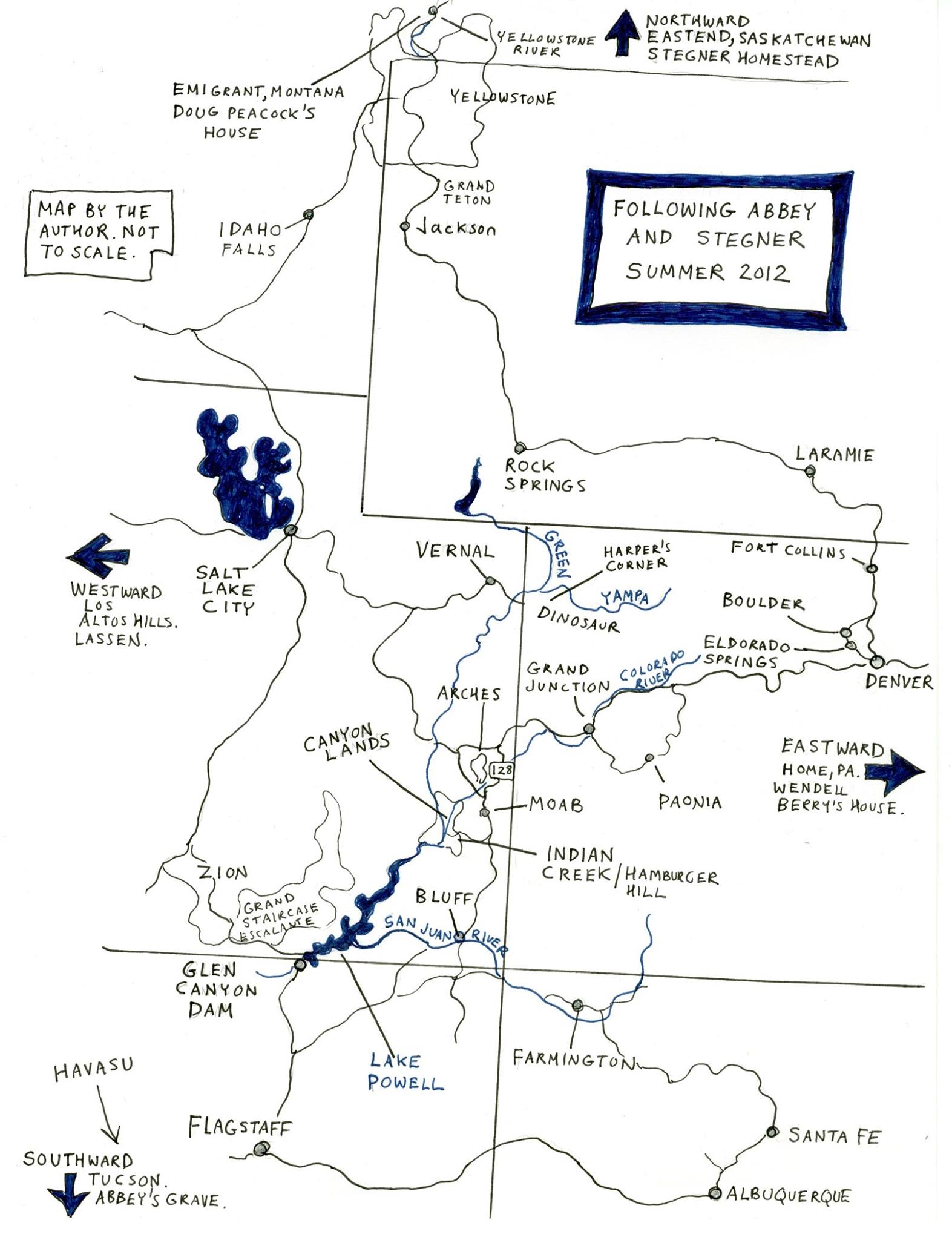

Enlarge

David Gessner

With All The Wild That Remains, Gessner has limned a quest for truth, and perhaps a bit of redemption, as he peers through the eyes of wise and voluble elders whose voices live through the printed word. As such, it’s a classically western construct, and Gessner, no shrinking violet, asks tough questions and doesn’t shy away from delivering the news.

That he would tackle Abbey and Stegner at a time when the West in general, and California in particular, confront their fourth year of drought and the Sierra Nevada snowpack is the leanest in recorded history, seems especially propitious, given that both authors propounded on the aridity of the West, and questioned the sustainability of life west of the Hundredth Meridian.

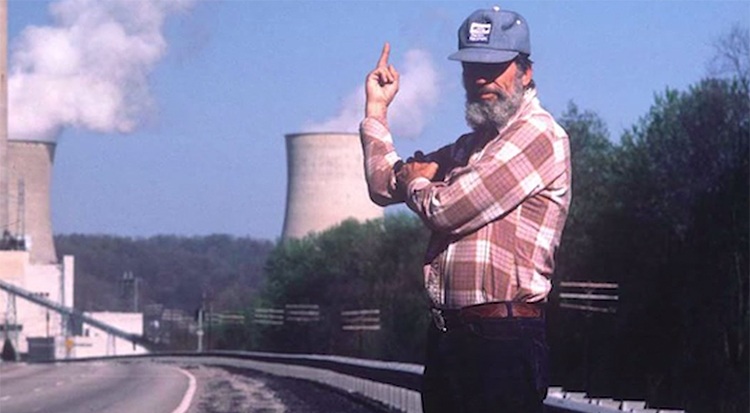

Stegner presaged that the lack of western water would risk the region’s livability, and worried that one day its thirsty chickens would come home to roost. Abbey shook his head and rolled his eyes as he witnessed road building, dam construction, and nonstop development, and worried, strenuously, that the many mouths and prodigious thirst of an ever-growing citizenry out west would outstrip nature’s supply, and prove the ruination of the landscape he deemed sacred. He decried growth, procreation, and man’s presumed dominion over nature. Both men lived in the West for most of their lives, Stegner in a home in Los Altos Hills near Stanford University, and Abbey variously in New Mexico, Utah, and Arizona, which is where he died. Abbey’s voice of perturbation contrasted with Stegner’s quieter and behind-the-scenes efforts to reform environmental practices; both made persuasive cases for wild domains as havens of saneness in an ever lunatic world; Abbey, prominently, through his books, like The Monkey Wrench Gang, and Stegner more quietly but no less effectively through his many novels, his famous “Wilderness Letter,” and the assistance he gave to then Secretary of the Interior, Stewart Udall, in crafting verbiage that would inform the 1964 Wilderness Bill.

Enlarge

The writings of both men changed lives; in Abbey’s case, perhaps, the taking up of arms, and in Stegner’s case, “connecting the dots,” as Gessner puts it, between “land, economy, resources, geographies, and cultures,” a mental model taken to heart by at least one of the country’s most influential spokespeople for wilderness, Wendell Berry, whom Gessner visits early on in the story. Berry credits both Abbey and Stegner for “lighting his way” as a writer, but perhaps it was Stegner who influenced him most, because, as Gessner quotes, “Wendell Berry had said he wanted to take Stegner’s ideas and try them out in his own neck of the woods…”

Enlarge

Fast forward to Gessner’s American West. All the Wild That Remains doesn’t just confront the ravages on the landscape due to climate change; as literary heir to both Thoreau (whom Gessner once described to his daughter as “the man who ruined daddy’s life”) and Michel de Montaigne, Gessner has used his books as a kind of gestalt. He of course owes a literary debt to Stegner and Abbey: Gessner is inspired by Abbey’s inclination to disturb the system and also Stegner’s inclination to work within it; Gessner harks to the voice of a renegade but also to the voice of a buttoned-down professor. EarthFirst! vs. the Sierra Club. Dylan vs. Seeger.

Abbey and Stegner were two of the most resounding of the many voices that have rung through of the American West, ultimately conjoined in their philosophies, and it’s this dynamic yin-yang Gessner attempts to reconcile in the book.

Enlarge

At the beginning of his journey west, Gessner received an e-mail from the environmental writer, Terry Tempest Williams, who offered what Gessner called a koan of sorts; she characterized Stegner as the radical and Abbey as the conservative, a notion inverse to the one most people hold about the two men. Gessner periodically revisits Tempest-Williams’ proposition in the book, and concludes that Stegner’s radicalism stemmed from his rootedness and devotion to home and work and family – steadfast and resolute – rather than restlessly searching for the Big Rock Candy Mountain.

“Wilderness is our first home,” writes Gessner, “the laboratory where human beings were created, where the human genome was hammered out over millennia, and that essence does not suddenly change in a hundred years because someone invented a car or computer. Our needs are still the same.”

Indeed, in All The Wild That Remains, Gessner makes clear, as did both Abbey and Stegner, that a little bit of wild goes a long way.

INTERVIEWER

We’re drying out here in the American West. Great timing for the book.

GESSNER

Yeah, yeah. Well, I thought about that. Somebody mentioned the snow pack in the last couple days. I have so many good buddies who are moaning and groaning in the Northeast about record snow. They mentioned that the snow had been weak out West and I had this simultaneous reaction of, “Oh that’s sad and it’s good.”

The, “Oh good” was for the book, but also for the warning factor of “Let’s face reality.” I just went down to the Gulf to do an article for Audubon about the five-year anniversary of the Gulf spill, and my main interview subject was playing the classic conservative, using the “Well it froze over in Lake Michigan last winter” defense. That’s the problem when you have the big winters: the [deniers] come in with that bullshit.

INTERVIEWER

I don’t know how you classify a book like All The Wild That Remains, but you’re mashing up genres. I imagine that you made conscious tradeoffs between biography, memoir, travel and environmental writing. How do you find the sweet spot when you’re trying to weave this kind of narrative?

GESSNER

It was a very conscious thing, partly motivated, to be completely frank, by the fact that for the first time I was working with a big New York publisher [Norton] and the interest there was more towards biography than memoir. Also, most people who probably read All The Wild That Remains aren’t going to be familiar with my work as a whole. I feel like I tried to make stuff pretty personal and sometimes that’s a way to pull people towards larger ideas or things other than the personal. Sometimes it’s because I like personal writing and so the biggest thing here was the ratio of the “me” to the two men and the subject.

Enlarge

Clark Vandergrift

INTERVIEWER

At the same time, you’ve got a powerful point of view and a large presence. And you show yourself at play, enjoying the landscape in these vast wildernesses of the American West, whether you’re looking out on a panorama or floating down the San Juan River, or mountain biking in the Canyonlands, and you leverage those moments to reflect on the state of the West.

GESSNER

I was just talking to my friend, [writer] Brad Watson, last night and we were saying the book didn’t really need a third large personality. It was making my stuff interesting but I wasn’t on stage with Stegner and Abbey. They were the stars. I’ve done that with other books, like my book about John Hay and The Prophet of Dry Hill where I consciously decide to pull back a little bit.

There’s a great quote from A.R. Ammons: “I look for the shapes things want to come as.” This book evolved in that direction where it seemed that it would be a false note for me to go, for instance, on a tirade when I have the world’s greatest tirade [writer] in the world in Abbey. I let Stegner get us to a point and to bring it into the present. But I don’t want to steal their thunder. This is a book about them, not about me. It’s book nine for me and the previous two have been a whole lot of David Gessner going off. He will certainly be back, knock on wood, for the next one. In a way, if anyone even thinks about me at all, they probably think of me more in the Abbey tradition than the Stegner tradition. I don’t think about myself that way.

Enlarge

INTERVIEWER

That’s interesting, given your body of work, which some would consider, ahem, nontraditional.

GESSNER

I acknowledge that Abbey was an influence on me, but as I say in the book, I didn’t read a word of him until I was 28. The humor and the ribald stuff comes more from Phillip Roth than it does from Ed Abbey. That was my early, big influence, like Roth and Vonnegut and those [authors].

I came to Abbey as somebody who was already regarded in my [peer] groups as an Abbey-like figure. I was this guy wearing a leather jacket who played a hippy sport, who drank a lot and said whatever came to his mind, so it was weird to encounter Abbey. I just reread the thing about reading him when I first moved west and the main influence that I remember is starting to eat refried beans. [Laughs]. I loved this! I had already been a reader of Thoreau and Montaigne so I loved to see a modern writer, a relatively contemporary writer, taking those techniques and using them in 1970, and that I could use them in 2000.

When Annie Dillard wrote Pilgrim at Tinker Creek, she worked toward two books: Walden and Desert Solitaire, and she looked at Desert Solitaire as an example of how you could write a Walden today. Abbey was helpful in that way, but in terms of influence, other than our relatively eccentric personalities, the thing Abbey and I share is a strong voice, even though they’re pretty different. Abbey’s appeal is in the emphatic and mine is in equivocating; there are a lot of buts and howevers.

INTERVIEWER

I was just going to ask you that actually. You make the “on the one hand, but on the other hand” move really well.

GESSNER

That’s how I think. Part of me thinks like, “Fuck ‘em,” but then there’s an instant qualifier that comes in, in a way that’s different. I don’t want to get too self-referential, but I think for Under The Devil’s Thumb, my second book, Luis Urrea said it was partly like reading Abbey and it was partly like reading John Cheever.

INTERVIEWER

Yikes.

GESSNER

He said it was just this weird combination.

INTERVIEWER

More Cheever than Abbey, then.

GESSNER

Yeah. And I didn’t grow up with a father who was radical. One of the interesting things about this book for me is figuring out where I stand politically. Because a lot of non-radical young people read Abbey and say, “Oh I’m a radical.” And they’re not, really. Not most of them, anyway. Putting these two together was interesting for me in terms of defining where I am in terms of that. My hope would be my other readers would say, “Okay, well, there’s these two poles, like where do I fit?”

Because a lot of non-radical young people read Abbey and say, “Oh I’m a radical.” And they’re not, really.

INTERVIEWER

You serve up the Terry Tempest Williams koan pretty early in the book – the one about Stegner being more radical than Abbey. Did you come away from your journey convinced she was right?

GESSNER

The original title of the book was Properly Wild, and the whole idea was how can I be a wild man in the sense that I want to be, which is staring out at the marsh right now and trying to get outside of myself on my daily walks — even though I’m walking a dog, not climbing a mountain. How can I do that and be a good man — in ways that Abbey wasn’t, frankly — to my wife and to my daughter and to my students and to people that I deal with in general. I think in many ways Abbey was a good man, but what is interesting [to me] and what continues to be a pressing question, is to try to handle all these bullshit responsibilities at school, miles to go before I sleep sort of stuff. Sometimes I’m like, “I wish the fucking Internet had never been invented.” But the truth is, on my normal day I get in a couple of hour walk with the dog and I write for a few hours and I usually read for an hour or two. It’s just a less radical, sexy picture of what it means to be wild.

There’s a little bit of a trope in a way. We know the radicalism of a Wendell Berry. We know the radicalism of home, and we understand it that way, as a movement in the nature writing world. It was a movement that from Gary Snyder on, is really contrary to Ed Abbey, because Ed Abbey is more like George Stegner [Stegner’s father, who was a wanderer], in terms of always looking over the next hill. So in that way Stegner’s radicalism comes from his idea of commitment and home. Home is important to me, too. It’s like it took me a while to shake off some of the Abbey and realize that.

Enlarge

INTERVIEWER

It seems that to me that you walked away from the book with greater respect for Stegner.

GESSNER

Yeah, I would like it if the book read that way, but I’ve always been a huge Stegner fan. Crossing To Safety might have been the first thing [of his] that I read. The narrator is this giant workaholic and I know I say at some point in this book that work has been salvation for me in a way that Abbey, whether it’s rhetoric or not, never truly regards it. I think that’s one of the things I talked about is how leisure or loafing is Abbey’s province, whereas work is Stegner’s. This might go way back to having Walter Jackson Bate as my professor in college, and his biography of Samuel Johnson, but I’ve always liked the realist vision of human personalities and psychology. If you’re ever in a relationship or a marriage or for that matter, if anybody observes you closely, they know that “you’re no hero to your valet;” much of your life is spent in crappy moods and fighting demons.

If you’re ever in a relationship or a marriage or for that matter, if anybody observes you closely, they know that “you’re no hero to your valet...”

INTERVIEWER

Normalizing the less-than-glowing personal narrative, then.

GESSNER

I’ll always remember that someone asked Samuel Johnson, “I’m having these impure weird thoughts,” and he said to them, “Well, seven-eighths of my thoughts are like that.” And yet, with that, [he could] be a decent person and writer: taking that as the realistic face. I think with Abbey, particularly with young readers, they begin with the romantic face and in the Havasu chapter, for instance, with Abbey, I talked about how he was more a realist than we know. He knew that all that loafing and the, “Oh, look up at the stones and full moon and it’s so beautiful,” could lead down to dark mental places. He was a realist, but his followers are often romantics. With Stegner, the realism is what excites me…or what we call realism; who knows what’s realistic? To me his description of life, particularly the biography of Bernard DeVoto feels familiar, which is to say, any day could drop me into the abyss, and I’m going to work my ass off to keep above it. But that’s only part of the day. You might go for a walk and have great moments outside of yourself, be with your kids…but there’s that element of nose to the grindstone.

INTERVIEWER

Did Stegner remind you of your father?

GESSNER

I think he does have my dad [in him], and this may go back how people perceive me too, but people who knew my dad would perceive him more as an Abbey character. There was a lot of drinking and just blunt, sometimes outrageous statements. My classmates in college loved drinking with my dad, who was the president of a textile machinery company. They’d be drinking with him and they’re like, “Oh my god, it’s like being with a regular guy.” Part of that was alcohol, but part of it was just a basic directness and bluntness which both men had, more obviously Abbey, but Stegner could cut to it, too.

INTERVIEWER

In watching Stegner on YouTube – especially the Night in Day interview you talk about in the book – it’s clear that he didn’t suffer fools.

GESSNER

Lynn Stegner, his daughter in law, said to me about that interview, “That was an aspect of his personality.” Like you said, he doesn’t suffer fools. He was not afraid of just cutting [people] to the quick at times.

INTERVIEWER

I want to revisit this notion of loafing vs. work. Do you see backpacking or other adventure sports as loafing?

GESSNER

That’s a great question. I don’t see it as loafing. Lawrence Rust Hills has a great essay in How To Do Things Right comparing Montaigne and Thoreau. Montaigne is the loafer, and Thoreau is in shape … for all the fact that we wish we were at the pond living the simple life. Those walks are four hours long and there’s a vigor to them, so they’re more Stegnerian than Abbey-esque, basically. Say you were going to take your 14-year-old son backpacking: a lot of the day is spent breaking down the tent, putting up the tent, and hiking. It’s not very loafy. In terms of bringing kids out into the natural world, whether it’s how vigorous it is, or whatever it is, it’s obviously so huge and it’s so important right now as a counterbalance to [computer] screen time. My daughter is 11, we bought her a computer for Christmas, and there’s a “down the rabbit hole aspect” to it that we’re combating with outdoor activities as much as we can.

I’m all for loafing, but as I wrote in my first book, my dad bought a hammock for a house on Cape Cod, and he sanded it and painted it and screwed it in and all these things, but I never saw him lie in it. Not even once. I’m of similar temperament.

Right now I’m sitting in the writing shack that I describe at the beginning of All The Wild That Remains; this is my daily equivalent of loafing. It’s 90 minutes within a vigorous 24-hour day. If somebody said, “Here’s a billion dollars. You don’t have any responsibilities; all your goals are fulfilled, so I want you to hang out in the shack for a year,” that would be a pathway to depression for me.

I guess what I’m saying partly is that I grew up in the remnant ‘70s, the remnant ‘60s, of the ‘70s and idealized things like Hugh Prather’s Notes to Myself and On Becoming a Person and all this stuff and I felt like, well I’m kind of lame the way I can’t really just be. I’m not Taoist enough. It took me a while to get to know myself and know that, yeah I can do that, but it’s in counterpoise to exertion and effort. In a way, that’s a nice description of the book. Not that Stegner’s all effort and Abbey’s all leisure, because that’s not true; but finding yourself by looking at others, that kind of thing.

It's sustainable for Wendell Berry, I guess, but it ain't for me.

INTERVIEWER

Another popular book around that time was Jonathan Livingston Seagull. I suppose you could substitute writing for flying. There’s a playful and ambitious quality to both.

GESSNER

I’m considering proposing a joint biography of Montaigne and Thoreau where the trip, the journey, would be a year sitting in the writing shack, viewing the traditional seasons throughout the year: a year unplugged with Michel and Henry. My wife said, “How would you do it?” I said that what I’d probably live my current lifestyle, which is getting up and writing and exercising and walking and having a reading period and probably continuing to teach and having a period of the day when I check Facebook. But I’d probably hire a grad student to do triage and to tell people that “He’s not available, he’s doing this project.” My wife said that’s cheating. “That’s not right. You can’t do that, if you’re going to do it.” I said, “Well I’d rather do that, which is real and sustainable, than the gimmick of just going totally offline for a year, because there’s no way that’s sustainable.” It’s sustainable for Wendell Berry, I guess, but it ain’t for me.

It gets really dangerous when your whole life becomes a video game and you’re always clicking and checking. I had an editor say to me recently, “For this piece to be most successful …,” and then parenthetically define successful as getting the most hits and views. That’s kind of a non-Thoreauvian definition.

INTERVIEWER

Taking the time to reflect, alone, especially in a wild setting, is powerful medicine. One of the most powerful moments, I suppose, of an Outward Bound expedition, for example, is the solo. The participants have been traveling through a wilderness in a small group for weeks, and at the end of the program each student spends three days alone. They’re often asked to forfeit flashlights, watches, and other technology — and those solos are often the most profound – even life-changing – three days of the entire experience.

GESSNER

Yeah. I’ve always needed to be alone for a certain number of hours a day, like writing and walking. I paddle from my backyard right here over to Masenboro Island at night. [Being alone] has always been a pressing need. What’s interesting for me is that it either isn’t a pressing need for most people, or they don’t get that it is a pressing need. In the instance you’re talking about its enforced, which is great.

I won’t go into the old curmudgeonly rant against cell phones and everything else, but it does seem that there’s no time for brooding, mulling, digesting, and I think that’s a reasonable worry to have for a lot of people. I teach with young writers, for them not to be doing that, it’s like, “How the fuck are you going to think things through if you’re not doing that?” I don’t know, to me it would be impossible.

INTERVIEWER

Both Abbey and Stegner spent time alone. They had their own writing shacks…

GESSNER

Yeah in fact I visited Stegner’s in Vermont. It was kind of awesome.

INTERVIEWER

You saw Abbey’s as well, didn’t you?

GESSNER

Yeah, well, I saw one of his, the one near Ken Sleight’s, and peeked at the one behind the Tucson place, both of them.

Yeah, they did [spend time alone]. One thing that occurred to me during the writing of All The Wild That Remains is that Stegner was always out of his time. He was probably most in step in the ‘50s, but then he was a little ahead of his time, because, like DeVoto, he was doing conservation stuff.

Abbey got lucky, because his writing naturally dove-tailed so well with the ‘60s and early ‘70s and as you probably know he said, “Hunter Thompson is the only journalist I really admire,” and there were parts of him that fit perfectly with that time, where for instance, it would be hard to imagine him attracting the readers he has right now. It’s interesting, because as a writer, I’m aware that it’s not just a book that you write; it’s how it gets out to the world. His might not have been successful had his message not coincided so well with the idea of freedom and wildness the way it did in the ‘60s. I’m thinking of Desert Solitaire, in particular. That isn’t to take anything away from Abbey’s books.

I think that last time I saw you I mentioned the line about, “That’s the cabin where the man lived who ruined Daddy’s life,” about Thoreau.

INTERVIEWER

Your generation attended kindergarten and grade school in the radical ‘60s, got their drivers licenses in the ‘70s, and came of age in the “Greed is good” ‘80s. How did growing up during that time mold your sensibilities as a writer?

GESSNER

I think that last time I saw you I mentioned the line about, “That’s the cabin where the man lived who ruined Daddy’s life,” about Thoreau. That was happening when I was 16, 17, so it’s 1979 at a New England prep school where it feels like it’s 1967. Everybody’s got long hair and nobody’s wearing uniforms anymore and there are girls there. Wow! Fear and Loathing isn’t written until ’71. A lot of the music that we associate with the ‘60s is still coming in in the early ‘70s.

So I think it molded me hugely to have that. Ronald Reagan’s ascension was a big part of my life; he was the main president that I drew as a political cartoonist, but what I hated was, of course, “Greed is good.” I’ve written about how the retreat from Carter’s presidency occurred in large part because he advocated moderation and restraint, and then suddenly Reagan comes in and says, “Let’s party…There’s no problem, there’s no oil shortage, whoo, let’s go nuts.” I was obviously very critical of Reagan, but I wasn’t critical of the real world rolling-your-eyes at the excesses of the ‘60s and some of the ‘70s, in terms of hippy-dippy philosophy, because it goes right to Abbey-Stegner again. As I said, I’ve got as much Stegner in me as I have

Abbey, and Stegner hated the ‘60s. He thought it was phony baloney, pie-in-the-sky stuff. Even Abbey made fun of hippies or any kind of a joiner and any excess, but his notions of anarchy and freedom fit well with those times. I still have that in me. As far as a pro athlete goes, give me Ken Stabler or Dave Cowens or Pete Maravich [laughs]. Give me people without muscles and with long hair who’ve got a little bit of Thoreau in them. I love that. That was part of the fun in the book too, was to go back to that time and say, “Yeah, shit, I wish I was part of that, too.”

INTERVIEWER

You took time off after Harvard to play Ultimate Frisbee. Obviously, the notion of play and sport were really important to you. Talk about this notion of play in your life and how it’s manifested in your leisure and in your writing.

GESSNER

I think I have a decent metaphor for that. I’ve been redrafting the Ultimate Frisbee essay [from Sick of Nature] into a memoir lately and one of the reasons I like it is it’s a good parallel with writing. From the time that I graduated from college at 22, until I published my first book at 35, I was doing two things that the world thought were ridiculous: I was playing Ultimate Frisbee seriously, which for most people sounds like an oxymoron, and I was writing a books that I really didn’t show anybody. Everybody was like, “Oh you’re a writer, well what do you write, and where do you publish?” I was like, “Well I don’t really publish yet.” So both things were a strain in that way.

I wasn’t naturally a non-conformist; I wanted to be a superstar.

One of the epigraphs for the book is Emerson’s: “Who so shall be a man must be a non-conformist.” I wasn’t naturally a non-conformist; I wanted to be a superstar. I became one out of necessity of having made these two bizarro choices. What I did during my time as an Ultimate player — and there were many driven Ultimate players, which may sound kooky to people who don’t do it, even though they were only known in the world of Ultimate — there was a sense of wanting to be famous within that world, a winner within that world. What I would do is play for the top four seeded teams. I’d play with the Boston team and go to Nationals and do all this stuff and then the next year I would quit and play with the goofy team, teams I called “The Popes,” or “Mother Throws Best,” or all these weird teams, partly because I wanted to try to write and it was hard to commit to two big things. But as far as the metaphor goes, that was the year of play and goofiness, and actually my throws got better during the play year. I’d suddenly throw these crazy blades and overheads. So there was a play year and then there was the serious year, so I think I’ve always had those two aspects in my work and in my life in counterplay. One of the reasons we love Desert Solitaire is it’s goofy in a way. [Abbey] will just go off on these things, and even though it’s deadly serious sometimes, at other times it’s just jokey. That kind of writing, whether it’s Tropic of Cancer with Miller, or others, has always appealed to me.

INTERVIEWER

Stegner and Abbey appear to occupy opposite poles in terms of lifestyle and voice. Did you learn anything about where you fall out along that spectrum?

GESSNER

I think so. I think I am less inclined to want to wander off with my goat herd and my pipe and live a pastoral existence. Again, I wouldn’t call them the Abbey-Stegner poles, but I would say they’re like what you were describing as the play pole and the dedicated, serious pole. It’s always been fun for me to bounce back and forth between the two. It’s a continuation of my book My Green Manifesto in that way: backyard wilderness is pretty damn good and the month I get to go live in Boulder in the summer is pretty damn good, but I have no fantasy about doing either wearing my sheepskin and just diddling away my time. It’s been helpful in letting me see how I need both poles. “Know thyself” sort of stuff.

Also, I’m older. I’m 54. I just had my birthday, and one thing I did for myself during my birthday week was look at old journals. I saw that this tension [between work and play] has been going on for a long time and it will probably go on until I die. A little self-awareness about this tension is helping me appreciate, for instance, my teaching job, which Abbey would scoff at and say, “Oh, man, I gotta get out there and live with no one else around.” And sure, if I ever get a full sabbatical year I’d love to do that for a month or two, but I don’t imagine that as an end beyond this. I think it’s a re-learning of things that I re-learn again and again, which is what I need, and what I fantasize about, and what the real mix is for me.

If you look at this Annie Dillard article in Harper’s, it’s fascinating how unnature-y that year [at Tinker Creek] was for her. I sit out here and look at the marsh – I mean, granted, we’re in a subdivision and there are houses around — but it’s not bad. I’ve actually been thinking lately, “Holy shit, I walk in the woods for two hours every day.” That’s pretty good.

INTERVIEWER

I’m not sure I’d describe the book as an encomium to a middle path, but maybe it’s about finding a happy place between the two extremes represented by Stegner and Abbey.

GESSNER

I don’t like the phrase because it implies compromise, but yes, to some degree that’s what I’m talking about. One way it did help me too, is defending my mature, less radical politics. That was a good thing. Writing the book also made me feel crummy about how non-political my life has been. What I’m hoping is that the books going to do well and that’s going to segue into some activism for me. Not to make excuses, but one of the reasons for my relative lack of activism is because I’ve moved to a place that isn’t my place to defend. I’m down in North Carolina. I tried to do that a little bit with the coastal building with [Professor] Orrin Pilkey and that stuff. I’m not living in a place in a way that I would be on Cape Cod or in the West where I’m driven to defend it… and that’s an excuse. Stegner and Abbey did things other than write, and that’s extraordinary in this day. Writers always say, “I’m just doing my writing,” and neither Stegner nor Abbey would have that as an excuse.

INTERVIEWER

How do you think Abbey and Stegner would have felt about latter-day activism, such as it is? You talk about a bit about Tim DeChristopher’s skewering of the system… but how about 350.org or how Yvon Chouinard uses Patagonia as a vehicle for environmental reform, or the Occupy movement — all of which are less strident than Abbey might have cared for, but it seems to be the brand du jour nonetheless.

GESSNER

I see them as that. I don’t think Abbey would have. If he were the Abbey we know and love, he would have scoffed a little about the current organizations. Having said that, I think they are an evolution of what he was doing. I remember Tim DeChristopher saying how the big difference was that their old narrative was to monkey wrench in secrecy and quiet and not tell anybody. The current narrative is to film it and show it to people. I think that’s smart. I think that’s taking what life is giving you. We live in that kind of society and I don’t know that secretly putting sugar in a gas tank is going to help very much but maybe like I think I bring up the movie, [the television reality show] Whale Wars.

Like I said, I think Abbey was lucky that he arrived on the scene when he did, and his writing fit the times, and served a huge purpose. I think he would have a hard time in today’s political climate, not being immediately pushed over for an extremist.

Enlarge

INTERVIEWER

You expose the American West’s troubles, but would you live there?

GESSNER

Yes, I would, because it fits so well with aspects of my personality, like being outside and finding time alone. And even though it’s the fastest growing region of the country, you still [have solitude]. When Hones and I were driving to our trip on the San Juan River I think we passed three cars. [Laughs] You have moments where you’re like, “Wow, this is different than North Carolina or Massachusetts.” So I would.

Again, the Stegnarian concerns come in; my daughter has lived her whole life where we are in North Carolina. I come from a family that moved from Massachusetts to North Carolina, when a lot of the kids were in their early teens and it really had a bad effect on the family so that would be a real concern of mine, is raising my daughter in a consistent place she thinks of as home. But if it were just me, are you kidding? In a second, I’d go. It’s extremely attractive to me as a place and unfortunately it’s extremely attractive to a lot’s of other people too. [Laughs].

INTERVIEWER

And yet you make it clear that you can find wild wherever you are – even in your own back yard.

GESSNER

Yeah, totally. I’m looking out at a creek where I can paddle from here to an island with no homes on it, where I can camp, and I’ve used it as a jumping off point. Is it my dream place? No. Politically, it’s getting more conservative. I never thought I’d live in the South but, in a way, I’ve even made that into a lesson for in terms of the fantasy place versus where you are. Yeah, I would rather be living in, probably, in Colorado or maybe Cape Cod number two. But this is where I am and I’m trying to make a good life out of it that involves writing and teaching and the natural world.

You’ve got all these romantic notions of the wild, then you thread them through the more realistic Stegnarian notions and try to make them come into play in your daily life. The thing is, you think of Abbey as the guy who was out there all the time, but Stegner ran every river and backpacked in all these places and spent time out there and you don’t want to underrate him in terms of getting out there, because he did.

INTERVIEWER

Where or what is all the wild that remains?

GESSNER

For me, it’s daily wildness, to find a way to integrate it and make it part of my life.