IT HAPPENED ON A CRISP SAN FRANCISCO EVENING. February of 1968 at the Carousel Ballroom. Jerry Garcia and the Dead were deep into “Morning Dew” to “Dark Star.” The band was locked in tight, and the crowd was locked into the band.

Doug Robinson, the 23-year-old wanderlust California climber, he of compact build and mellow mien and soft grey-blue eyes, was there, returned from a summer of guiding in the Eastern Sierra, grooving at 13,000 feet on angularities of frosted granite. He lived in the Haight, and was a year away from completing the English degree he had been chipping away at for years. But now he was spinning to Garcia’s arpeggios, a couple hundred mics of Owsley on board. Each time he turned toward the stage he saw a mélange of tones wafting from Garcia’s Gibson as waves of violet and pink, like the Northern Lights.

If not exactly habituated to synesthesia, Robinson was certainly no stranger to altered states of mind. He most often felt it in the mountains when thick into an adventure on rock, snow or ice. Even when running long-distance on backcountry trails. Granite walls sometimes fell away from him in the midst of a climb, or he’d sense himself as the locus of an entire cirque, or peer through the dendritic mass of a snowfield and perceive individual crystals winking in the sun.

He was tinkering with his consciousness by subjecting his body to the rigors of an outdoor life, which he understood made him feel good. And quite alive. As did the vegetal analogs: weed, peyote, psilocybe cubensis, and lab-concocted LSD, of course. And wasn’t the climbing literature itself full of references to the transcendent and miraculous, rife with allusions to personal transformation from the rigors of the ascent? These were tropes Robinson understood as both a climber and a writer.

He couldn’t help but wonder how it was that the drift of consciousness evoked by a tab of Owsley could be so similar to that unleashed by surging into the alpine zone. What stuff could exist in one’s body to bring on such states of grace? Might the body manufacture its own admixture of molecules not dissimilar to those of lysergic acid, psilocin, psilocybin, or even marijuana — our personal stash of feel-good hormones — which either singly or in combination flipped the visionary switch?

What gets climbers high? Half a century ago, Robinson set out to answer that question. And this year, at 68, he’s serving up the long sought-after answer in The Alchemy of Action, a 179-page book chock full of brain science, adventure writing, and a goodly dose of philosophy.

…..

BY 1968, BOTH THE SCIENTIFIC community and the counterculture were well acquainted with the effects of acid and their organic kin, mescaline and psilocybin. Anecdotal data were abundant in the Haight, where Robinson lived. And the science was there too, wedged in the stacks of San Francisco State College, if you knew where to look for it: research conducted from a time when the word “psychedelic” wasn’t drizzled with blacklight paint or sheathed in paisley. It was simply a scientific term coined by a British psychiatrist.

Robinson was an English major, not a biochemistry wonk. But compelled to decrypt a link between externally consumed hallucinogens and those that he was sure his body manufactured when he ran and climbed, he pored through obscure medical journals, grokked findings from the nascent field of neuroscience, and dug into newly discovered compounds affecting the central nervous system. And of course, conducted his own participant-observer research.

Fortunately for Robinson, the reading wasn’t all molecular diagrams and descriptions of neurotransmitters and receptors; the psychedelic literature was full of graphic diary entries of of biochemists who became accidental anthropologists, like Dr. Arthur Heffter, a German research pharmacologist who in 1897 isolated mescaline in the peyote cactus and became the first of a line of button-down scientists who drank their own Kool Aid and journalized their findings in pornographic detail. The Swiss scientist Albert Hofmann synthesized lysergic acid in 1938 as an analog of ergot, but was ignorant of its potency until April 16, 1943, when he accidentally dipped his finger in a new batch of the brew. Three days later, he intentionally ingested 250 micrograms to gauge the effects of a threshold dose, and wobbled home on the trippiest bicycle ride yet known to humankind.

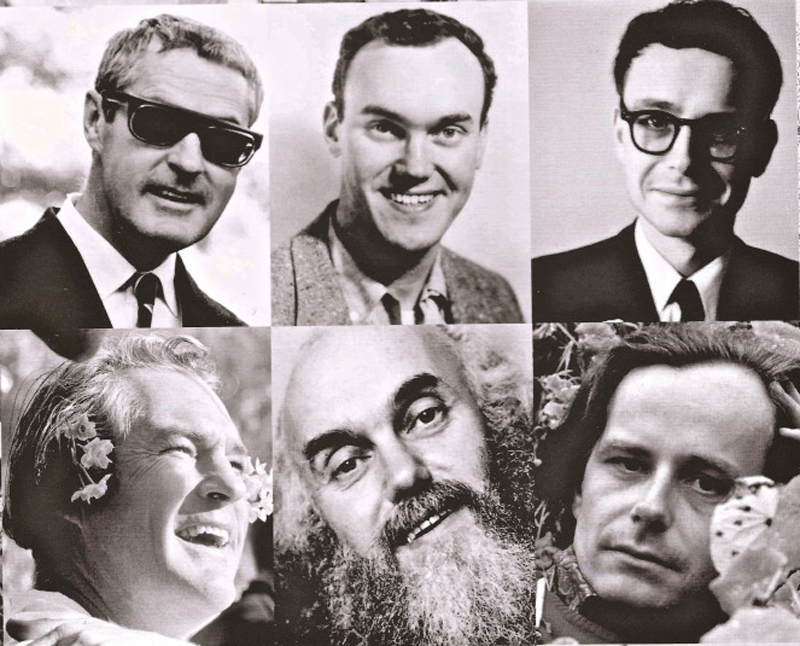

In the mid-20th century, N,N Dimethyltryptamine, or DMT, the psychedelic half of ayahuasca’s two compounds, was isolated in plant material at about the same time the CIA, through its MK-ULTRA study, dosed volunteers on acid through various fronts such as, say, the Menlo Park’s Veteran Administration Hospital, where a young writer by the name of Ken Kesey offered up his central nervous system to science, and subsequently wrote One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, decked out Furthur and staged the Acid Tests. Aldous Huxley’s 1954 mescaline-influenced Doors of Perception introduced the notion of tripping to the general culture, and in 1960, Timothy Leary, Richard Alpert (who would later change his name to Ram Dass) and Ralph Metzner launched Harvard’s Psilocybin Project to study its affects on student volunteers, and soon after, their Cambridge colleague, Jim Fadiman, a doctoral student, lit out from Harvard for a research gig at Menlo Park’s International Federation of Advanced Studies, and ushered 350 people through their first acid trips at $500 a throw.

Enlarge

Although adrenaline, noradrenalin, endorphin, dopamine, serotonin and oxytocin had all been discovered and were shown to tickle the central nervous system, relatively little was known about how they affected the mind. Even the opioids — the endorphins — had yet to be discovered. The case for human-produced hallucinogens – the so- called endogenous psychedelics — was, at the time, intriguing, but murky.

There were, however, clues that they existed. Serotonin, for example, was remarkably similar in molecular structure to LSD. DMT had turned up in human urine, blood, and lung tissue, but no hard evidence existed that the brain made its own. These were the compounds Robinson sought, but could not find. And back at SFSC’s stacks, he stumbled on Hoffer and Osmond’s The Hallucinogens, an omnibus of all known such compounds, whose authors suspected that psychedelics swallowed, insufflated or injected by humans were attaching themselves to receptors designed to capture home-grown compounds.

“I turned a page, and here was a molecular diagram with adrenaline at the center, and there were arrows radiating out that showed its relationship to other compounds,” Robinson says. “One of them was mescaline, and there was a big question mark on the arrow – ‘Does this happen?’ Nobody knew, but the guys who wrote the book were sure calling the question.”

Bereft of hard data, but long on self-knowledge, and armed with enough evidence from the climbing literature, and of Huxley of course, Robinson composed an essay about climbing’s ability to imbue the climber with an acute sense of perception, and made the provocative proposition that naturally occurring hallucinogens were to blame. Or to thank. He submitted the piece, “The Climber as Visionary,” to Steck and Roper at Ascent in 1969.

“There is an interesting relationship between the climber-visionary and his counterpart in the neighbouring subculture of psychedelic drug users,” wrote Robinson, who noted that climbing, coupled with its anxiety, “produces a chemical climate in the body that is conductive to visionary experience.”

The article was well received by the climbing community, and Robinson was hailed some years later in Chamonix as “Le Visionaire.”

I met Robinson in the summer of 1995 on an assignment for Climbing magazine. Even then he was hard at work on The Alchemy of Action, and told me then that he could glimpse the end of the project. We became friends. In the intervening years I’d occasionally ask him how Alchemy was coming along. He’d usually say he was making headway on it, and little more. But three years ago he indicated that the project was very much alive and nearly complete. He began emailing me chapters to read, and he asked for feedback. Sometimes I’d proffer it; at other times, too cowed by the biochemistry, I’d demur.

When he presented me with a copy of the galley proof of the book, I was surprised to see a blurb attributed to me on what would become the book’s cover.

“Our guide is a friendly and folksy roshi whose light touch helps his readers tackle technical ground.” I had written that passage for my blog, Sustainable Play several months prior, when previewing The Alchemy of Action.

Robinson-as-roshi, for all its attempts at piquancy, isn’t mere hyperbole (roshi is an honorific bestowed upon the leader of a Zen Buddhist community). If Camp IV wasn’t exactly a Zendo, it was comprised of a tight-knit clan living a spare and simple life, and Robinson gave voice to its culture, making the community more conscious of itself, by throwing down challenges and offering up a koan or two. In 2010 the American Alpine Club honored him with the H. Adams Carter Literary Award.

It’s been a while since Robinson busted out tablet cracking prose, perhaps preferring to instruct by doing, as he did in 1973, when he made the first hammerless ascent of Half Dome’s Northwest Face with Dennis Hennek and Galen Rowell. In 2007 he returned to Half Dome, but this time to its south face. Intent on filming the FA of a Sean Jones big wall (fast wall?) route, he helped Jones rap bolt the thousand foot headwall that began where the natural features ran dry on stone so unfeatured it would accept no hooks. Growing Up went at 5.13, AO – a stout climb, a controversial climb to be sure, and the top-down tactics snapped heads. If he wasn’t exactly the co-author of the route (he has made clear that the decision to rap bolt was Jones’s to make), he certainly acted as a scrivener. Their reasoning at the time was that they wanted a safe route — a Yosemite classic — that strong climbers could tackle without maiming themselves.

When the greater climbing community learned of the ascent after Robinson’s account ran in this magazine, some defended the route, while others called for his pillorying. He could have let the article speak for itself and moved on, but instead he quietly entered the scrum on Supertopo’s forum, made his reasoning transparent, encouraged debate, owned up to mistakes, and held out an olive branch to those who savaged him.

“All glories to Doug Robinson, our kind and gentle teacher,” wrote the Valley veteran Werner Braun on the Growing Up thread, amidst the shitstorm that raged there, tipping his hat to Robinson for comporting himself non-defensively, and with an intent to instruct.

He eventually removed himself from the bright white spotlight of Half Dome’s south face to attend to his family and dig into The Alchemy of Action, and increasingly repaired to his mountain redoubt at 10,000 feet in one of the Eastside’s grander canyons. He acceded to the entreaties of friends and admirers, and donned his trademark white flat cap with the Armadillo totem pinned to the brim, to lead them through and atop the sinuous rock ridge sprawling above the well-known Buttermilk bouldering circuit anchored by the Peabodies: Smoke’s Course. He skied a new route across the Sierra – the Otto – peripatetically puttered on rock wherever he could find it, and, of course, he researched science for Alchemy. And he wrote. And kept on writing.

…..

I SAVE ROBINSON’S EMAILS, because they’re more than mere shorthand; they’re epistolary. Our correspondences increased markedly in 2011, and it was obvious he was very close to tying a bow around the book. And after years of work, Alchemy had finally revealed itself.

The message of the book was clear enough: climbing, or nearly any sustained pursuit, “leavened with a dash of fear,” as Robinson put it, got you high. No toke or tab necessary. Not even desirable; Robinson explained how the body is equipped with its own feel-good hormones, which either singly or in combination flip the bliss switch – a visionary switch — when humans engage in an extreme activity requiring silent attention. For years he had referred to climbing as a moving meditation, and now he described the powerful drugs manufactured by our own bodies that unlocked the treasure of transcendence. We’re hard-wired to experience visionary states; we must be. After all, you make the drugs, they exist for a reason, so you might as well harness their power and enjoy the ride. Climb rock, or if that’s not what you’re into, practice zen archery. Either way, you’ll evoke the compounds that’ll tickle your spiritual G-spot.

But what are they?

Hanging out with him in his Rock Creek a few years ago with requisite dense cup of Major Dickason’s Blend, he described five.

“So noradrenaline is the first big hormone in responding to action sports. The second one is dopamine – it’s our pleasure hormone. It says, this is fun. We’re enjoying this. We’re enjoying it enough that we want to repeat it, we want to keep going, we literally want to get addicted to this activity, to whatever it is that’s kicking off our noradrenaline and our dopamine. OK. The third one is serotonin. I think of it as equanimity. Serotonin does a lot of different things in our brains and in our bodies, but let’s just focus on this one part here first. Equanimity. The ‘roll with it’ hormone. I can handle this. Really feeling competent here; I can do this. ‘Don’t sweat the small stuff, and it’s all small stuff.’ That’s the feeling of serotonin. So add that in to the hormonal cocktail. Now we’ve got a pretty good juice going here, you know we’re high-functioning people. We’re in a flow state. Now notice perhaps that those three hormones are actually the big three that run the mood of our brains. Whatever we feel as ordinary consciousness is a lot of what we’re feeling is those guys at work. Especially when we’re high functioning. The higher functioning we are, the more they roll out and juice who we are. If you didn’t have those three guys you’d gut the system; we wouldn’t be awake or alive, really.

“OK – then there are two more ingredients in the hormonal cocktail, and these are the controversial ones, because they’re two psychedelic compounds. One I’d already identified as a brain hormone, and the other one, about to be; we’re a little ahead of the curve here. The one that’s already identified is called anandamide; it is your brain’s own equivalent to marijuana. Kind of surprising, maybe, but if you think about it, we have receptors for marijuana in our brains, or it wouldn’t do anything to us.

“The final ingredient is DMT. DMT is the most potent psychedelic known to man. It changes the way we see the world, it changes our thinking, it changes our mood, if you take a lot of it, it can cause hallucinations, which is one of the qualities of psychedelics which is part of the definition of being a psychedelic. But we’re talking about small doses here. Very small. Turns out to be made in our pineal glands, which are right in the middle of our brain. Tiny thing, about as big as a grain of rice. It trickles out DMT – it’s actually a very small amount. But the stuff is so powerful, and it trickles out just millimeters away from receptors in our emotional brains, right in the center of our brains that are sitting there, eagerly waiting for it – this is a system that has evolved over some time – and the DMT is changing our perceptions. Some people think – I think – this is responsible for a lot of the tone of ordinary consciousness.”

Enlarge

Robinson makes clear that the high of this hormonal Fab Five, when it comes, is far subtler than the E-ticket ride of say, 100 mics of acid, a puff of DMT, or even a hit of Purps. No visits from Mama Ayahuasca. None of Terence McKenna’s squeaking, self-transforming elf machines. The state of grace Robinson describes is more one of enhanced visual acuity, a slight sensation of floatiness, an alert mind, a forestalling of time, and an amplification of self-efficacy, all activated by the saucy concatenation of noradrenaline-dopamine-serotonin-anandamide-DMT — stirred, not shaken, mind you. Famously, Yvon Chouinard experienced such a state. In the 1966 edition of the American Alpine Journal, he wrote that after seven days on the first ascent of El Cap’s Muir Wall, he began to notice the individual crystals in the rock and tiny bugs that were all over the wall. “While belaying, I stared at one for fifteen minutes, watching him move and admiring his brilliant red color,” wrote Chouinard.

With Alchemy, Robinson believes he’s succeeded in squaring the psychopharmacological circle as it were, since even with the gains in neuroscience, so little is known about brain, mind, and consciousness. He fully expects that The Alchemy of Action will one day read much as “Visionary” does today: still relevant but incomplete with respect to the science, which is in such a state of flux that just a few years of research could reorder our understanding of what makes us tick.

I recently asked Robinson what difference the whole business made. As in, he’s spent 44 years figuring this thing out. So what?

“You can’t raise your consciousness until you know how it works,” Robinson said. “Let me turn that on its head. You can better raise your consciousness the more you understand how it works. So if you get it that action sports are getting you high, that climbing gets you high, and you begin to break that down and see what the hormones are behind it, then you can play with it.”

And playing with it, it turns out, might be as simple a nostrum as moving your body over interesting terrain. If you choose rock, great. And if the stone happens to glow while you’re moving over it, well, all the better.

Robinson’s new book may surprise readers with its analytical superstructure. Though couched in casual meter, it’s essentially an explanation of the science, and because he’s making a case for this particular hormonal quintet, it’s necessarily mechanistic. Sure, there’s evocative adventure writing when he recounts outings with friends, or describes the extreme adventures of others as living examples of the book’s thesis (and at least one chapter that seems out of place for a book targeted at the climbing community), and there’s a goodly amount of medical history and basic biochemistry which read like literary non-fiction. But by the book’s final chapter, he all but confesses his discomfort with all the reductionism and persuasion, and urges his readers to seek their own truth.

“Gnosis, not logos,” he writes.

BUT WHAT ABOUT THE LOGOS? Is there anything to his claim that our bodies are hard-wired to get us high?

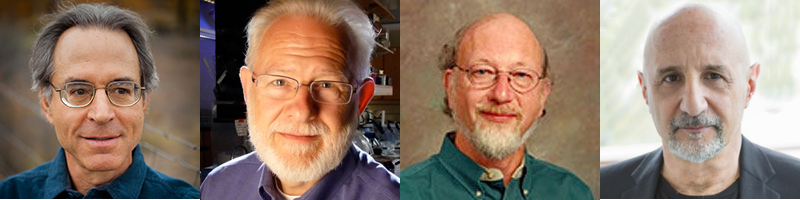

“I think what he’s saying is reasonable,” says the ethnobotanist and biochemist Dennis McKenna. “The important thing to remember is that we’re biochemical engines, because we’re made of drugs.” McKenna should know. The younger brother of the well-known psychonaut Terence McKenna, his recent book, The Brotherhood of the Screaming Abyss, describes their Amazonian expeditions of the early Seventies to explore and consume DMT-laden plants. Today McKenna’s Heffter Research Institute is making strides in the use of psilocybin as an adjunct to talk therapy in treating alcoholism, depression, and drug addiction.

“I always tell my students, ‘Forget drug-free America You are drugs. As a result, being this neurohormone-driven, neurotransmitter-driven regulated piece of meat here, at some basic level we’re a piece of animated flesh. We certainly know DMT does increase under stress-like situations like birth and death.”

“You’re in a situation, you know, say you’re mountain climbing,” says David E. Nichols, Purdue professor emeritus who has arguably synthesized more psychedelics than any living biochemist save Alexander Shulgin. “The view is beautiful. The air is cold. It’s exhilarating and the stress is producing all of these things. I don’t have any problem buying that at all. But I don’t think you have to invoke DMT. I mean, that’s where I kind of say, you know, okay, stop there. Stop right there.”

Nichols, who prides himself on being a rigorous psychedelic scientist who doesn’t truck with woo-woo theories, has no issue with the notion that we make DMT in our brains; he simply believes the quantities to be too minute to produce a psychedelic response. Besides which, it would be nigh impossible to measure, even if we did.

Enlarge

“You’d have to put what’s called a microdialysis probe into somebody’s pineal gland, and then you’d have to take samples while they were running and physically exerting, and that’s never going to happen,” he says.

“Is there an area of the brain that’s very tiny that’s close to the pineal gland that nobody has discovered is really the key regulator of consciousness? I don’t think you’ll find anybody who studies cognitive neuroscience that would say that. Is it theoretically possible? I don’t know. Maybe. But you know, there’s nothing that suggests that there is a neural area that is right downstream of the pineal that’s like a master controller for all of these interactions that go on to maintain consciousness.”

“There are people though, who would probably say, ‘Oh yeah.’ Rick Strassman would say, ‘Oh yeah.’ Nick Cozzi would say, ‘I think it’s possible.’ But you know, it’s like a subculture. It’s not in the mainstream.”

Nicholas Cozzi is the Director of the Neuropharmacology Lab at the University of Wisconsin Madison, and Robinson makes much of his findings in Alchemy; Cozzi discovered INMT in humans, the enzyme behind the manufacture of DMT. I find him in his lab, and I tell him about Robinson’s cocktail. As Nichols suggested he would, Cozzi had no problem with DMT’s inclusion in the brew, but he didn’t exactly support Robinson’s suggestion that it’s the first among equals in dictating the tonality of an adventure athlete’s brain.

“I mean, I don’t necessarily disagree with that list, he said. “But I don’t feel like we can ascribe all these things to this chemical or that chemical in the brain. I think that’s too reductionist for my tastes.”

I ask him to elaborate.

“You know, I don’t think we know enough about it. I kind of see it more like a symphony. What we’re kind of trying to say here is what notes contribute to it. Well…they all do. Then they move through time. There’s an ebb and flow, just like in a musical piece. And so they’re all important. Maybe music is a good analogy, because music can make you feel certain ways. It can make you feel sad, it can make you feel happy. Maybe there are certain chords, certain mixes of neurochemicals that favor one or another mood. There’s got to be 100 neurochemicals known. Not just the ones you’ve mentioned, but all these peptides, too. I couldn’t even name all of them that are all part of the mix.”

I realize that Cozzi, who told me he’s climbed a bit, and refers to himself as a spiritual surfer, is saying in so many words that the components of consciousness are likely ineffable – at least based on the current state of the scientific art. To suggest that a single note, or even a five-note chord, might account for a gestalt, doesn’t do that state of grace justice.

So I tracked down the grand panjandrum of DMT research, Rick Strassman, who plays somewhat of a starring role in Alchemy. From 1990 to 1995, Strassman injected DMT into human subjects in a study at the University of New Mexico’s School of Medicine, the first federally sanctioned psychedelic research of its kind in years. Strassman currently serves as the director of the Cottonwood Research Foundation, which sponsors DMT-related research. Last year, one of his researchers did insert a probe into a live rat’s pineal gland, and found traces of DMT, the closest science has come to making the human DMT hypothesis concrete.

I reached Strassman through his website, and described to the DMT maestro himself Robinson’s DMT hypothesis.

“It’s an interesting theory and worth testing,” he wrote back.

I responded with the observation that he hadn’t answered the question. Was he hedging with “maybe,” or was it a polite “no?”

“Maybes are what get tested in research protocols,” he replied. But then, “Pineal DMT is so close to critical brain sites that it may exert a psychedelic effect before it’s broken down.”

Which is precisely what Robinson is saying. And what Nichols said Strassman would say.

When I shared with him Nichols’ view that the theory is untestable without compromising the brain of a human lab rat, Strassman suggested a process by which DMT might be isolated during exercise without penetrating the skull.

…….

“YOU CAN PROBABLY ANTICIPATE THE QUESTIONS I’m about to ask,” I say to Alex Honnold, priming him for what’s to come. He’s apparently hunkering down in his van on raw October evening in Yosemite Valley.

“Yeah, yeah, but let’s hear them.”

I ask him whether he’s ever experienced an altered state on the rock.

He thinks about it a bit. Struggles with it.

“I mean, I’m trying to think of something good,” he says. “But like, honestly I don’t, really. Like for me, fatigue is always like a linear…like, I start out with energy and then I get less and less as I go, and then eventually I’m just really, really tired. You know, but I never get all like, psychedelic or anything.”

I ask him about soloing. Whether his mind feels different.

“I would just describe it as normal. You know, paying attention. I don’t know…I don’t know. I mean, is it supposed to be different?”

I can’t help myself. I laugh. Out loud. Certainly not at Honnold, nor at Robinson’s theory. It simply strikes me as humorous and entirely possible that what others would take for a positively numinous experience is Honnold’s steady mind state.

My chuckle apparently jars something in him.

“I guess for really hard climbing I’m definitely more focused. You know, everything sort of falls away a little bit.”

He told me that he often loses track of time when he’s soloing. And then he described a February solo of Zion’s Monkeyfingers in full conditions. He was utterly alone. It had started to snow, and hard. He dispatched the technical climbing, and with 1500 feet of snow-covered third and fourth class slabs to gain the rim. In a near hypothermic state, and disoriented by the deep snow covering the rock, Alex Honnold was afraid he might die.

“And then I wound up finding a bighorn track, just like a single set of prints from a bighorn, going up basically the exact same route that I had to take. And I basically followed this one set of prints all the way up to the rim, and I was already in sort of a weird state, you know? Anyway, so I followed these tracks all the way up, and I was like, this is totally how Native Americans have spirit animals. And I was like, this is how people find religion.”

Or how religion finds them: often alone, in the wilderness, mind already primed and the juices already flowing due to the rigors of an extreme journey, either inward, outward, or both. Brain chemicals? How couldn’t they play a role in experiencing an epiphany?

“I do talk about those types of things,” says Peter Croft, referring to altered states of consciousness brought about by moving through the mountains. “You know, the amount of focus it takes, and oftentimes risk seems to be an essential part of it. It just makes you have to focus that much more, and you’re so much more into the mental and physical act rather than the technical thing with gear and all that kind of stuff. So it seems to me that the more runout climbs or soloing, I get that kind of thing more, and maybe part of it is that it’s more continuous movement. It’s really all about the act of climbing. One time that I can think of that was especially weird, I guess, was I was in Yosemite and I was doing a bunch of big climbs in a day. And the final one I did was going up on Snake Dike, up on Half Dome.

“Anyway, so I get up on that and it’s really late in the day. I can’t remember; the sun was probably going down. But I’d been climbing all day long. I start climbing, and I stop looking up or down, and it felt like I was on a moon that was just rotating and all I had to do was just look straight ahead and everything in my peripheral vision was super clear. But I wasn’t looking anywhere, and it was – this moon was basically spinning slowly and I just kept on climbing and climbing, just to stay basically in the same place. Kind of like in a sort of hamster wheel turned inside-out or something, and it just had this feeling like I could just go on forever.”

I ask him whether he actively seeks to replicate that experience.

“It’s one of the reasons I like going for big days by myself, is that feeling.”

“In the biography of Albert Hofmann, they called him ‘Mystic Chemist’ but when he was being a chemist he was being a chemist and when he was being a mystic he was not being a chemist,” says Ralph Metzner, author, anthropologist, psychologist, and one of the world’s most traveled psychonauts. “He was able to function in both realms but the mystic realm is not a realm that you go into voluntarily. It’s like Aldous Huxley said; it’s a virtuous grace. It’s given to you no strings attached. Climbers don’t go up there in order to have that experience. They go up there because, as Mallory said about Everest, ‘Because it’s there’ and the runners — they’re not running because they want to have that experience either. They’re just running.”

…..

IT’S LATE OCTOBER, and Robinson wants to hike into the Sierra’s Palisades to show me a new project on the north face of Temple Crag, the prominent spire that acts as a gatekeeper to the upper cirque of the subrange’s peaks, the densest cluster of 14,000’ summits in the Sierra. As we set out from the trailhead to follow the north fork of Big Pine Creek, I realize we’re walking into Robinson’s sanctum sanctorum: the Palisade Basin has developed his skills, molded his thinking, brought him home to himself.

The days are short and Third Lake is already in shade, although a shaft of light still gleams through the 14,000’ curtain forming the upper amphitheater. We stop short at Second Lake. Temple Crag looms above, looks like a short walk away, save for the devious talus slope separating us from its base. The new route, Mountains of the Moon, takes a line just to the left of Dark Star. Instead, we hunker down and steep in the raw grace of the place.

Traveling with Robinson through the Sierra is an object lesson in “set and setting,” Timothy Leary’s notion that the tonality of a psychedelic experience hinges as much on the tripper’s mindset and his environment as on the quality and dose of the drug itself. As I look over at him beholding Temple Crag, it occurs to me that if getting “high” is a state of grace cooked up by our transcendent hormones, then it makes perfect sense to work a life around the activities and places that evoke them. Robinson’s done that, and through his writing, and by the way he’s lived his life, he’s encouraged his community to do the same.

Robinson and others have observed that those whose obsessive trials with turning lead into gold were, in fact, transforming themselves; true alchemy takes place within the mind and heart of the alchemist. Or as Terence McKenna put it, the human body itself is an alchemical vessel. Whether your laboratory is high on a wall, or on the firm floor of a Zendo during the final hours of a seven-day sesshin, Robinson wants you to know that when that transformative slurry of your home-made drugs kick in, and you find yourself in the midst of “it,” rest assured that you have evolved to enter the visionary realm.