IN AN OBSCURE WASH in the high Mojave stand two domes, their north faces steeped in shadows. Four friends scrutinize the rune-like creases on the northeast face of the northernmost monolith, searching for a path up the steep wall. They are young, in that boggling interval between adolescence and manhood. Much later, they’ll remember the time as a golden age, and how their fellowship produced some of Joshua Tree National Park’s greatest climbs.

In that spring of ’78, Craig Fry, David Evans, Randy Vogel, and Spencer Lennard would work on the new route, a project that would take three long days spread over seven months. Only Evans and Vogel would finish it. On that day, finally on top, they’d gaze at the yawning expanse of corrugated rock and twisted shrubs, sort out their gear and start their descent. Already the details of the climb would have begun the slow, sinuous slide into memory. Over the next several decades, remnants of the experience would gyre within their minds, where all recollections transform, increasingly, into artifacts of imagination.

Time and memory are true artists; they remould reality nearer to the heart’s desire. — John Dewey

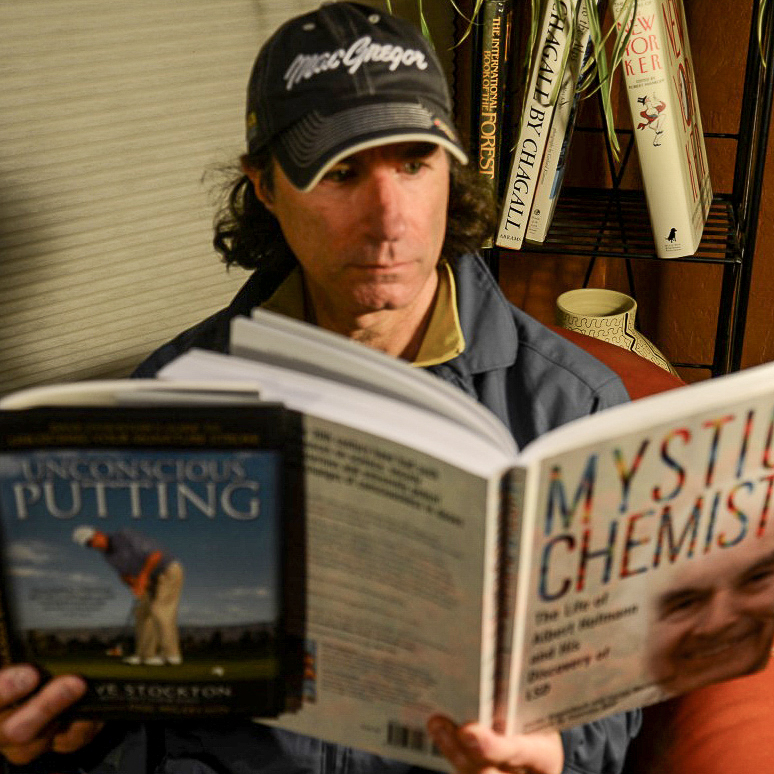

IN 1987, THE COVER of Mountain magazine featured two climbers performing a kind of pas-de-deux across an immense wall of muted ochre rock. The dark-haired belayer lounged from a three-bolt anchor, and held the rope loosely while his blond-haired, balletic follower traversed a heart-shaped bas-relief. They each wore blood-red shirts and pants white as sun-bleached bone.

Enlarge

Photo by Galen Rowell

Figures on a Landscape: that was the name of the climb, as well as the title of the photograph. Galen Rowell had captured Skip Guerin and Ron Kauk as they repeated the route almost 10 years after the first ascent. A raddled copy of Mountain 114 made its way through the small, youthful San Diego climbing community of which I was a part. Intrigued and entranced by the photograph, we all talked big about becoming a figure on that landscape. Soon enough, I did.

I knew nothing, then, about the stories of Fry, Evans, Vogel and Lennard. But twenty-five years later, an online search led me to a climbing forum that contained a welter of conflicting narratives about the route’s history. The four men joked with one another, dissed and were dissed, and apologized in turns as they shared wildly skewed memories about the route’s creation. Intrigued—and then obsessed—I reached out to each of them to try to understand the fissures between a thing done and its telling.

It was cliquish as fuck-all. — Roy McClenahan

BACK IN THE LATE ’70s—when Joshua Tree was still “the Monument,” before concrete curbs kept Winnebagos from straying onto the fringe of the Mojave, before the Park Service built the new asphalt lots and prettied up the outhouses—a few dozen climbers from California’s Southland met every weekend in Hidden Valley Campground. They called themselves the Sheep Buggerers, the Joe Boys, the Scumbags, the Uplanders and the Orange County Crew. Like the famous Stonemasters who preceded them, these groups were mainly composed of middle-class suburban kids. Some learned to climb through the YMCA, others from big brothers, through the Scouts or from one another. All of them had spent time at Rubidoux, Corona del Mar, Stony Point, Woodson and Big Rock where they calloused their fingertips, developed their heads, but mostly learned to see.

During the warm months, they hung out at Tahquitz, Suicide Rock and Yosemite, but they spent the better part of their formative years in Joshua Tree. By day, they ventured onto crystal-studded granite and gritty slabs, their fingers numbed by north winds and their feet torqued into PAs or EBs worn several sizes too small. They swapped stories around campfires, celebrating bravery and upbraiding weakness. For some, this world was an escape from school, loneliness, abuse or ennui. For many, it was also about competition and athletic upward mobility. “We were freaks and outcasts,” David Evans told me. “It was widely accepted that if people were not slandering you, you were nobody.”

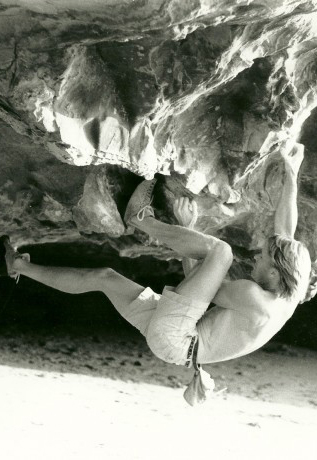

Enlarge

Craig Fry Collection

The Joshua Tree community upheld some of the most rigorous standards in the United States at the time. On difficult routes, first ascensionists confronted what seemed an existential dilemma: retreat; drill while balancing on a wispy stance, facing the potential of a serious fall; or drill from a hook. Whatever choice they made could define them: to themselves and to everybody else. The “Mobile Harassment Unit” threw catcalls at lead climbers: “No mistake or big pancake,” “Finger locks or cedar box.” For Southern Californians, John Bachar embodied the puritanical ground-up ethos more than anyone else. John Long called him the “Grand Templar of the entire movement.” Musing on Bachar and the other top Stonemasters, Evans remembered, “We didn’t want to let them down. You just couldn’t do it.”

By 1978, Evans, Vogel, Fry and Lennard were among the elite. Fry, age nineteen, a former high school pole-vaulter, had started climbing later than the others, but he’d reached 5.11 by the end of his first year on stone, and the Stonemasters named him “Rookie of the Year.” Evans, twenty, blond and easygoing, had scaled mountains with his father since age five. Lennard, twenty-one, a long-haired free thinker with perfect footwork, had flashed The Edge, Tahquitz’s fearsome testpiece, while some of his “betters” backed off and looked on. Vogel, twenty-four, was the group elder. “With a keen scientific intellect and the ability to debate almost anyone on any topic,” Lennard later wrote, “[Vogel] could destroy a person’s reasoning and leave them dead or begging for mercy.”

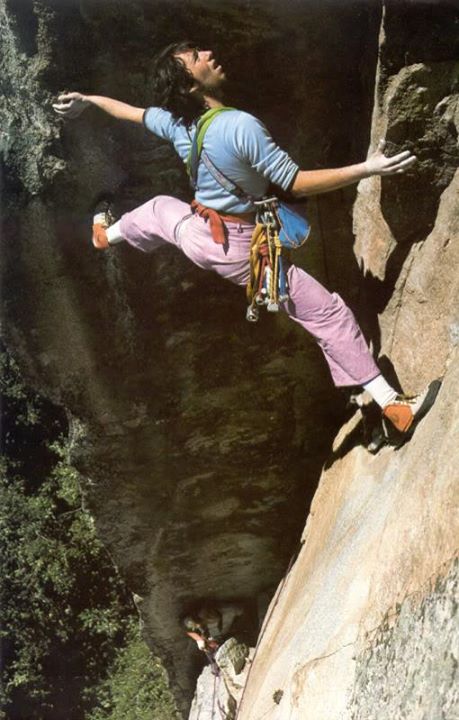

Photo by David Evans

Their partner Matt Cox passed around his careful notes of new climbs. After Cox left, Vogel kept adding to his records, collecting information in a spiral-bound notebook that he called “The Toad’s Guide” and that he’d later develop into his well-known guidebooks. Meanwhile, he brooded about the dome in the Wonderland of Rocks. There was a way to the top that looked hard but might be done in pure style—a chance to create a multipitch climb that said something.

Landscapes are culture before they are nature; constructs of the imagination projected onto wood, water, and rock. — Simon Schama, Landscape and Memory

THE WONDERLAND OF ROCKS is Joshua Tree’s emblem of wilderness, a twelve-square-mile granitic keep crosshatched with sandy washes and sharp-clawed vegetation threading hulking stands of quartz monzonite. Its labyrinthine jumbles resemble Stygian caves. Stunted oak and single-leaf pine cast eerie penumbras into deep alcoves. Ravens roost on varnished cliffs. There’s a sere light that lends itself to thoughts of older, spiritual journeys.

In the ’70s, only a few climbers ventured into the Wonderland’s depths. A handful of routes existed on South Astro Dome. Fry told me that he first glimpsed the line that became Figures on a Landscape from Such a Savage, a thin face climb that he and Lennard established in 1977. Vogel said he scoped Figures separately and showed it to Evans. Others likely ogled it too. “Anybody who was doing any of the routes on South Astro Dome would naturally just walk right by the base of the North Astro Dome all the way around,” Vogel explained.

Enlarge

Photo by Randy Vogel

There’s a big difference between admiring a block of stone for its beauty and seeing it for its creative potential. If you want to lay claim to the entire arc of a route’s authorship—from imagination to realization—then beginnings matter. And this, perhaps, is where the memory skew starts.

“The whole thing comes down to who was there on the first day,” Fry said to me at the end of an hour-long phone conversation. “That’s the way I look at it. It was me and Spencer there the first day working on it, and then I brought Randy and Dave into it and we worked on it. Then Randy ended up finishing it.”

I called Vogel. “Unlike some I don’t claim to have a perfect memory,” he said. “I know Craig’s memory is that I wasn’t there at that particular time. But be that as it may, that’s not correct.” As to the claim that Fry and Lennard put in the first few bolts alone: “That’s total fantasy.” I asked him if he was sure Evans was there. “Oh, God, yeah.” But in an account published in Vogel’s Joshua Tree Classics, Evans made it clear he wasn’t there. “Spencer, Craig and Randy had started the route a week or two before and placed the first two bolts on that day,” he wrote. When I got Evans on the phone, I asked him when he first saw the route. “All I remember is Randy showed it to me. It wasn’t the first day that people had been there,” he said with a laugh.

That left Lennard, who climbed only the first of the three days before departing for college. He wrote a farcical tale, freighted with fantastical imagery that he hoped would subvert the whole argument. (At one point, the late John Yablonski appears on the wall as a crab-clawed spider. In a separate account, Lennard suggests that Yablonski and Cox soloed the line long before either Fry or Vogel saw it.) “So I don’t really honestly care specifically who did what,” Lennard told me. “But I do remember Craig finding the route and bringing me out there and going up on it and putting some bolts in and realizing how amazing a climb this was going to be. I’m pretty positive it was just Craig and I.”

There are other disagreements: Vogel said that he drilled the route’s first bolt, but Fry claimed he did. Vogel said that Evans placed the second, but Fry told me that Lennard did. Evans produced photos that he claims showed him placing the third and fourth bolts, thus refuting Fry’s assertion that he placed one or both of them. There’s also confusion about whether the route’s second day of activity occurred in April or November and thus whether the summit day came after a summer-long or weeklong wait.

Lennard still views the debate as absurd, a niggling rift compared to the vibrancy of coming of age together in Joshua Tree’s Golden Era. Besides, asserts Lennard, their brains were snapped into altered frames while they risked their lives on those walls. “We just realized how powerful a medium it was: creating on rock…. We’re in another place. You’re actually in a Dreamtime. So in order to be climbing at that level, you really have to turn off your brain.”

Enlarge

Photo by George Meyers

Lennard left the area for college, so he wasn’t around on the second day on the wall. On that day, as they made their way to North Astro Dome, passing the Seuss-like plants and the lunar rocks, Vogel described his vision of unimpeachable style to Fry and Evans: They would use no hooks to drill the route’s bolts. All bolts would be drilled on lead from stances. Anyone caught hanging from a hook would be pulled off the wall. If that meant a horrific fall, so be it.

Either Fry or Evans placed the third and fourth bolts. Each one required twenty minutes of drilling with half-swings of the hammer, the bit nested between thumb and hand with remaining finger pads incised onto edges. Then it was Vogel’s turn. Above the fifth bolt, he launched across the traverse captured by Rowell’s photo. He slotted a rattly nut behind the flake and sidled up and right for about fifteen feet, when the rock steepened and the holds petered out. From there, he’d have to make a full-wingspan tilt for the rim of a ledge and try to mantel. A mistake would mean falling more than twenty feet before the nut popped and sent him for another forty-foot swing. Evans paced below, beseeching Vogel to find protection. Vogel retreated, ventured back, vacillated and returned to the flake.

Suddenly Fry and Evans heard the tapping of metal on metal, and they looked up to find Vogel dangling from a hook attached to the flake, drilling a bolt. They screamed at him, cursed him, and threatened to pull him off the route, which would have sent him swinging 40 feet . Vogel begged for mercy. They relented, allowed him to place two two quarter-inch bolts, and lowered him to the ground. Sobered, they retreated from the Wonderland.“It was probably the ultimate in hypocritical acts,” Vogel told me.

Fry, busy with schoolwork, asked Vogel to wait for a few weeks so he could participate in the route’s culmination, but Vogel and Evans returned the following week without him. I asked Vogel why. “My recollection is Craig didn’t drill any of the bolts on it,” he said. “So we kind of felt that given that, that his investment was less than ours.”

On the third day, Vogel tiptoed through the runout and slammed in a few bolts higher up. Evans led the corner to the top. They’d done it. Blinking in the desert light, Vogel had an intuition, already, of what the route might become. They’d been calling it “Monkey on My Back,” yet in his 1981 supplement to the Wolfe guide, Vogel renamed it Figures on a Landscape, inspired by an obscure film, Figures in a Landscape. The poetic new title, with the slight substitution of on for in, seemed to capture something essential to the art of climbing.“We were figures on a landscape,” Evans told me. The unusual beauty of the stern line so evocative of an abstract painting, the ground-up ethics (despite the hooks) and the relatively scant bolts turned it into a symbol that, with time, came to represent the zeitgeist of its era. “In the scope of things, it’s probably pretty insignificant to the world. But as a personal experience, it’s very significant,” Vogel said.

Decades later, as the popularity of Figures grew, so did Fry’s sense of betrayal. By then, he’d become invisible in its history—all the more painful since he believed he was the one who’d first set foot on the line. “I really didn’t care that much anymore other than having people say that it was Dave and Randy’s route,” Fry told me. “That was what kind of irked me, because no one knew the real story about it. Because only Randy and Dave were talking about the story, and they left me out completely.”

Following the usual convention, guidebooks listed only those present on the completed first ascent. Fry eventually aired his grievances on Supertopo’s forum: “The act of the first ascent was a team effort, Randy broke up the team, and took something from me that was important (as noted, one of the best routes in JT), that’s stealing.”

“Sometimes you don’t do things in life perfectly,” Vogel told me. “You can’t go back in time and change it, but you can acknowledge your mistakes. You can try to make amends with that.” He posted a public apology: “I am very sorry that we did not wait for you, Craig.”

That memory, the warder of the brain/ Shall be a fume, and the receipt of reason/ A limbic only. — Shakespeare, Macbeth

“IT’S A CRUMMY LITTLE crag climb in Joshua Tree, right?” Kerwin Klein said with a chuckle when I called him. Klein, a history professor at Berkeley, has written treatises on memory. As a student, he spent time in the Hidden Valley Campground. He’s climbed Figures on a Landscape more than once, and he even participated in the Figures Supertopo thread. I asked Klein what happens when historiographers are confronted with disparate accounts.

“People are deeply invested in the very idea of their memories as being these sort of precious, perfect, veridical records of what actually happened on the one hand, and little bits of their personal innermost being on the other. And that’s touchy,” he said. “Imagine we have a God’s-eye view of a camera that’s set up and following each of them for twenty-four hours a day and North Astro Dome for twenty-four hours a day. My guess is that no one account is actually going to come close to the sort of thing you could piece together from any version of those imaginary videotapes.”

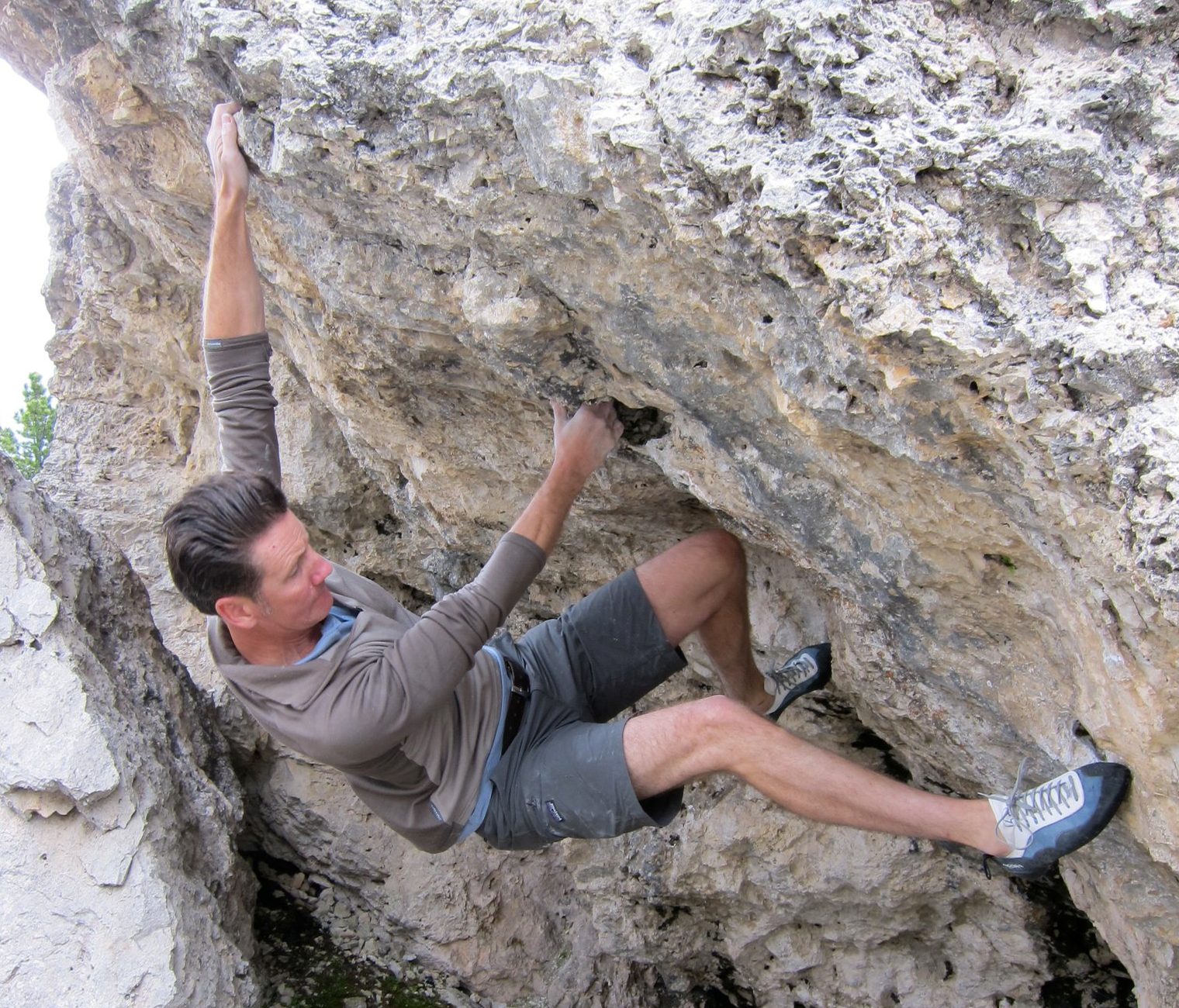

Enlarge

Kerwin Klein Collection

So, I wonder, does history matter in what could appear to be relatively trivial divergences of memory? “There’s two different philosophical questions,” he explained. “One is just a basic logistical technical question, which is how veridical is any given memory? And the answer is not very. We’ve known this for a long time.” The American Psychological Association estimates that one in three eyewitnesses identifies the wrong suspect. There’s little correlation, Klein added, between a person’s confidence in a recollection and its accuracy. “So that’s level one: the squishiness of memories. The second issue is what counts as history. We’re all following our bliss when we read about climbing history, right? It’s basically porn. Nobody has to demonstrate the significance of porn…. The same thing is true of what most climbers think of as history.”

Most lay climbing historians, he noted, gather narrative accounts without testing them. Academic historians critique sources, compare evidence and submit papers for peer review. Even so, the description of an incident can’t ever be fully definitive. Klein mentioned a classic example in Arthur Danto’s “Narrative Sentences”: prior to 1648, no one could have called the conflict between France and the Habsburgs the Thirty Years War. In other words, an actor has no knowledge of the swath of events that might unfold while she’s in the midst of them.

“So there’s a sense in which history is necessarily always constructionist and retrospective, right?” he asks. “And it’s informed by this sort of end that it’s driving toward, the objective, and by the sort of setting in which that objective emerges.”

The truth is not distorted here, but rather, a certain distortion is used to get at the truth. — Flannery O’Connor

OVER TIME, Vogel told me, he realized that the assemblage of the conflicting Figures stories might create an entirely wrong, but entertaining fable. I suggested that, woven together, the skeins of memory weren’t unlike Akira Kurosawa’s masterwork, Rashomon, in which four witnesses to a homicide relate wildly different accounts of how it was committed.

“I could only hope!” Vogel said with a chuckle. “But yeah, that’s kind of the idea.” In a way, that über-narrative already exists: the four versions are now “encapsulated in the climb”—part of the layers of myth that seem to permeate the stone.

Much of climbing history is preoccupied with first ascents, experiences that require a knowable chain of events to explain who got on top when and by what means. Yet if memory is so prone to distortion, how much of our canon can be verified? Should our accounts reflect a more honest appraisal of the limits of what we can know—the extent to which personal and cultural desires affect our perceptions? Individual recollections are frequently mediated by collective forces: group narratives, folkways, ethics, propaganda, competition, dogmatism, peer pressure and slandering—the kind of subculture prevalent in the Hidden Valley Campground. “Memory works a little bit more like a Wikipedia page,” psychologist and eyewitness-testimony researcher Elizabeth Loftus said. “You can go in there and change it, but so can other people.”

We all believe we know who we are—as communities and individuals—based on memories of who we were. But if a truth foundational to identity is proved false, then who and what and where are we? Adrift, we become exiles in our own skins. Desperate for definition, we often attempt to anchor to that which is solid and sincere and infallible. Climbers tend to return to stone.

When I asked Evans why Joshua Tree was so special to him, he replied, “It’s the lighting. It’s the shapes of the rock formations. But it’s really more all our experiences there. I wouldn’t say it’s part of our life; it is our life. I don’t know how to be any more emphatic about that. I dream about Joshua Tree.”

Everybody needs his memories. They keep the wolf of insignificance from the door. — Saul Bellow, Mr. Sammler’s Planet

IF, SEVERAL MONTHS AGO, you’d pressed me to recount the day I climbed Figures on a Landscape, I’d have told you that I had little memory of it, apart from my pride in a solid lead of the second pitch. I’d tell you that after passing the crux, I launched off on dozens of feet of incuts protected by a single bolt, and I built a belay to bring up my second, who wasn’t a regular partner, but someone I met in Hidden Valley Campground and never saw again. I’d tell you that we got to the top without any falls and hiked out of the Wonderland at dusk. I’d also tell you that my memory of Rowell’s portrait was far better than that of my own time on the wall.

As I researched this article, I’d been using Vogel’s newer guidebooks. Recently, I decided to take a look at his 1986 guide—the lilac one I used when I climbed the route. I pulled the book from the shelf, located Figures on a Landscape on page 380, and there I found a note, in a slanted hand unmistakably my own:

“3/89. Followed.”

This was, of course, impossible. I must have annotated the book some years after climbing the route, and somehow erred in my haste. “Led second pitch, followed first and third pitches”—that’s what I meant to write. Then I contrive a murky image of a young climber removing a gear sling and passing it to a faceless partner. Could it be? Definitely not. I recall too vividly the frisson of casting off on an up-trending traverse, the sure bite of varnished edges, the weft of purplish braids arcing from harness to belay while I expulsed the phantasm of a huge pendulum fall. Mostly, I remember transporting something ineffably precious from the Wonderland that evening and enveloping a life within it—not an experience with which I’d willingly part, then or now.

Did I lead the second pitch or follow it?

Did Fry and Lennard climb alone or were all four present on the first day of Figures?

There’s only one possible answer, of course.

Yes.

![]()

.

Brad Rassler’s writing has appeared in Outside, Sierra, Alpinist, Ascent, and other outdoor publications. Brad is the Editor in Chief of Sustainable Play, an online magazine featuring award-winning writing at the crossroads of people, planet, and play.

This story originally appeared in Alpinist Magazine (#52). Many thanks to Alpinist’s Editor-in-Chief, Katie Ives, who helped mold this piece, and to Adam Howard, Height of Land’s CEO, for his permission to reprint it.