IN THE PREDAWN hours of a recent midsummer day, Peter Mayfield walked through the skeletal remains of the Manzanar National Historic Site, the mothballed World War II Japanese internment camp located hard by Highway 395, in California’s Eastern Sierra. Seven miles distant, in serpentine repose, lay Mayfield’s objective: the Himalayan-scaled northeast ridge of Mt. Williamson, its 10,000 vertical feet of weathered granite stretching from high desert scrub to the 14,389’ summit — the longest ridge in the Sierra Nevada.

Glancing downrange, Mayfield could just make out the monolithic east arête of 13,225’ Mt. Carl Heller, bathed by the sun rising over Death Valley. Beyond loomed the summits of Mts. Russell and Whitney. With a three-day break amidst a packed summer schedule at his Tahoe-based environmental school, the Gateway Mountain Center, Mayfield set out to climb the four peaks, and return to Donner Summit in time to greet a new group of students.

But he seemed unable to pull himself away from Manzanar’s denuded cell blocks. He wandered through the ragged cemetery, its few barren gravesites outlined with cobbles, dimly aware of the susurrus of origami ribbons swirling from a lone Kanji-inscribed obelisk. Manzanar felt strangely alive, haunted. Eventually he made his way to the barbed wire fence ringing the compound, ducked under it, and struck out across the alluvium of Bairs Creek toward Williamson’s ramparts.

Three mornings later, Mayfield soloed the East Face of Mt. Whitney, the last of the peaks. Alone on the summit, he squinted eastward as the sun rose over the Inyos, and shifted his gaze to the north to behold the 30 miles of ridgeline he had just traversed, most of it over 13,000 feet. He had gotten what he had come for: Not glory — he had told only close friends about his plans. Not the summits — although he had scaled their technical east aspects without difficulty. He had come to the Sierra Nevada alone to sleep in the open, ala John Muir, cradled by krummholz and granite. “My life was changed by developing a relationship with the Sierra,” Mayfield says.

That relationship with California’s mountains has been redemptive, if not symbiotic. Some think he’s given back to the mountains more than he has taken from them.

“He has an ability to be humble and kind and generous with his incredible set of skills,” says Amelia Rudolph, with whom Mayfield founded the vertical dance troupe, Project Bandaloop. “He’s capable of doing things in the mountains few humans can,” she says, “and he’s of that elite group of climbers who has nothing to prove, so really it’s more about the generosity of spirit, and his wanting to give his gifts away.”

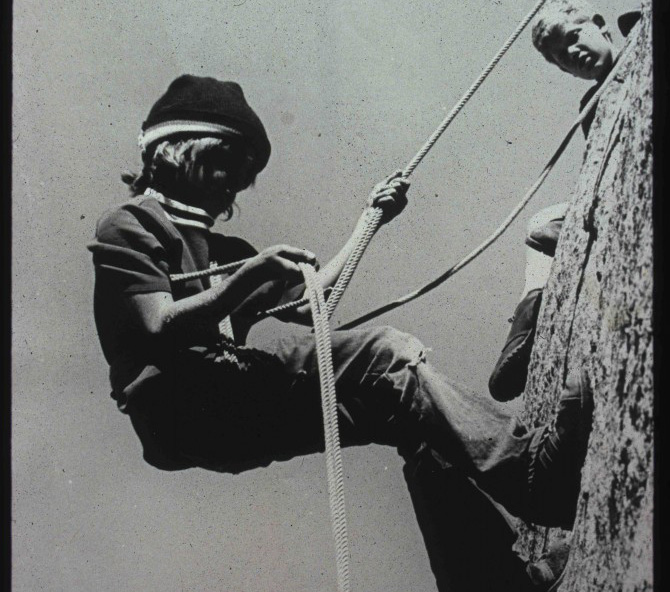

Mayfield was born in 1962, and was orphaned in San Francisco’s Presidio Hospital. He was adopted by a Sacramento-based psychiatrist and social worker. He described himself as an independent, precocious and outgoing kid, endlessly curious. “My parents were always negotiating my way into things I wasn’t old enough for.” When he was ten, he followed a YMCA camp counselor up Yosemite’s Monday Morning Slab. Years later, after his parents divorced, Mayfield moved into his father’s Grizzly Peak home in the Berkeley Hills. Walking by Remillard Park one day, he found strands of Goldline bristling from the rock, along with the members of the Sierra Club’s Rock Climbing Section (RCS), who had placed them there. He joined the group, became its best student. He peregrinated between RCS climbing outings and the bouldering scene at Indian Rock — climbers tended to belong to either one tribe or the other in those days — which is about the time he led the crux pitches of the Lost Arrow Tip on an RCS outing. At 15, he summered in Tuolumne, and by season’s end had led Piece de Resistance (old school 5.11c, probably harder), a bold ascent.

“I went to Yosemite full-time at 17 thinking I was going to spend a few years climbing hard before going back to school where I had thrived,” Mayfield wrote on Supertopo.com’s forum. “Met a cute waitress with an infant, and was soon a step-dad, homeowner in El Portal, and then a father at the age of 20. Quickly becoming a bit of a leader in the small pond of guiding and ski instruction, paradoxically, I spent my 20’s more grounded and ‘responsible’ than I have lived any time since.”

Meanwhile, he was putting up some of the neckiest wall routes in the Valley, teaming with Jim Bridwell to climb El Capitan’s Zenyatta Mondatta and The Big Chill on Half Dome. “He’s stronger than he looks,” says Bridwell, “and a lot of that is character.”

Enlarge

Jim Bridwell

Tent-bound with Bridwell on the Ruth Glacier in the late ’80s during an ascent of the Mooses Tooth, Bridwell described artificial climbing sculptures he had seen when climbing in Arco, Italy. Mayfield, then 26, imagined bringing the transformational experience of rock climbing to thousands of city-bound recreationists by building a climbing wall in the midst of the Bay Area. Afterwards, he raised a half-million dollars and created one of the country’s first climbing facilities in Emeryville. He called it CityRock. Mayfield’s creation – a workout facility-cum-climbing gym, offering yoga and instruction – was a precursor in form and concept to the 400 or so climbing gyms that now lay scattered across the country.

Eventually he returned to the Sierra, where he’s lived ever since. He recently turned 50. He still climbs and skis, but the Gateway Mountain Center gets most of his attention these days. His mission? “We’re opening young people’s hearts and minds to the natural world.” he says.

Some social critics have blamed helicopter parenting and computer screens for chaining kids indoors. “Our society is teaching young people to avoid direct experience in nature,” writes Richard Louv in his Last Child Left in the Woods. “Our institutions, urban/suburban design, and cultural attitudes unconsciously associate nature with doom. Well-meaning public school systems, media and parents are effectively scaring children straight out of the woods and fields.” Louv posits that alienation from nature “diminishes use of the senses, attention difficulties, and higher rates of physical and emotional illnesses.” Like a toxin that comes as a side effect of modernity, traces of that lack can be detected throughout humanity. Mayfield’s out to cure the world of that malady, which Louv calls “Nature Deficit Disorder.”

“Gateway Mountain Center enables kids to have a wilderness experience in a safe way,” says Al Adams, retired headmaster of San Francisco’s Lick-Wilmerding High School. “Just a baseline of connection to the environment and the outdoors is huge.” Adams, who has worked with Mayfield, was impressed with Gateway’s interdisciplinary approach to experiential learning, and by Mayfield himself. “The first thing that comes across when you meet him is that sparkle in his eyes that conveys the passion and clarity of his vision,” he says.

Enlarge

Eric Perlman

Terry and Alex Meadows of Kentfield, California, sent their son to Gateway’s summer camp three years ago. “Austin” suffers from Tourette Syndrome and ADHD, both of which have made him an easy target for bullying at school. Terry wanted him to try climbing.

“Peter showed me that I was welcome, even though I felt apart from the other kids,” says Austin, now 12. “You’d be there and no one would make fun of you and he’d support you and do everything in a nice way. He’s one of those people you can look up to.”

Austin thrived, according to Terry, and his transformation led Mayfield to seek funding to expand his work with the mental health care community, an approach that complements traditional mental health regimens. Gateway’s “Whole Hearts, Minds, and Bodies” combines outdoor adventure activities, nutritional counseling, academic tutoring, mentoring, and nature-based therapy to form the same kind of transformative amalgam that helped Austin. Mayfield says the mentoring element is key to success of the program. Studies have shown that one of the best predictors of resiliency in troubled youth is having a consistent, caring relationship with a non-parental adult.

“Nature’s peace will flow into you as sunshine flows into trees,” wrote Muir. Mayfield agrees. If he has his way, no child will be left inside. ![]()