FOR THE BETTER part of a day I’ve been drifting with Doug Robinson through his life, flitting from the Sierra to the Winds, from the Himalaya to the Eastside. Twilight filters through the windows of his Kirkwood, California vacation cabin and a flurry of snow dusts the window panes. Robinson sits exuding calm, all five feet five inches and 150 pounds of him, supple and lean at 51. He gives me his all with laughing blue-grey eyes, and latches on to every question, smiling at the memories that take him back 40 years.

It’s eerie, but somehow soothing – Robinson isn’t just listening, he’s running parallel to my psyche. With his hair and beard gone to white, he strikes me as a gentle diviner, able to see straight through to my pith. And then we’re silent for the first time in hours. The wood stove ticks with heat. His three-year-old son, Tory, lies curled asleep on his lap, and Robinson feathers his fingers through the boy’s blond hair, smiling at the miniature likeness of himself.

Robinson, as expected, begs off any greatness. Then I flash on a Bay Area magazine header from a few years back that referred to him as “King of the Sierra.” He may well be. After nearly 40 years of scaling its crags, skiing its backcountry, climbing its frozen gullies, living in its canyons, guiding, and writing, he’s covered the range as thoroughly as John Muir. And though he’s retired from living in its heart – he lives with his family on Northern California’s coast, next to a stand of old-growth redwood – his Sierran legacy is as enduring as a white bark pine.

Says Claude Fiddler, co-author of Sierra Classics, “Doug didn’t just climb and ski here – he lived here. Just like Norman Clyde. And for the few of us who have made the Sierra Nevada our home, his way of being in the mountains continues to inspire.”

Courtesy Patagonia Works

Robinson burst into the collective conscience – yes, conscience – of American climbers in the early 70’s with two bold strokes that changed the nature of the sport. The first was his essay, “The Whole Natural Art of Protection,” published in the 1972 Chouinard Equipment Catalog. In it, he urged climbers to use nuts, not pitons, to protect leads. And though he wasn’t alone – Royal Robbins and other progressive climbers believed that using nuts was the right thing to do – most climbers needed convincing. Nuts were considered dicey, not nearly as reassuring as a well-driven piton. Nuts upped the commitment level, and required redefinition of style and technique. Robinson urged both. His article was a polemic that used reasoning, imagery, and gentle badgering.

“There is a word for it, and the word is clean,” he wrote. “Climbing with only nuts and runners for protection is clean climbing…Clean is climbing the rock without changing it, a step closer to organic climbing for the natural man.”

The essay made the rounds of many campfires, sparked debate, and eventually won the day. “It revolutionized the whole getting-away-from-pitons movement,” agrees Yvon Chouinard, also a leading climber of the time, who was then manufacturing his “Stoppers” (a name coined by Robinson). The catalog was even reviewed in the 1973 American Alpine Journal by a young photojournalist and climber, Galen Rowell. Rowell wrote that the catalog “contains more information on the ethics and style of modern climbing than any other publication in our language.”

Then in August 1973, Robinson walked his talk up the Regular Route on the Northwest Face of Half Dome in Yosemite. It was a landmark climb, and one that catapulted the state of nutcraft into fast forward. It didn’t hurt that the climb was featured in the June 1974 issue of National Geographic.

Rowell had scored a contract from the magazine– his first big assignment – to document a Valley wall climb. He had one in mind: the Northwest Face of Half Dome, but needed partners. He had met Robinson in the Eastern Sierra, where they had teamed up on several first ascents. Consequently he wasn’t surprised when the soft-spoken Robinson and another clean-climbing stalwart, Dennis Hennek, balked at his offer to co-star in his story.

“Here I was, sharing a dream come true with Doug and Dennis, and all they could say was, “Wait a minute — this article could corrupt rock climbing,” says Rowell.

Robinson felt it would be unsporting and hypocritical to hammer his way up a big wall. Hennek agreed.

“So together we conjured the idea of how the story – if it were published – could be something that would advance climbing,” Rowell says. They made a pact to climb the route clean; they’d carry hammer and pitons for use only in case of emergency. Both Robinson and Hennek stipulated that the offending gear would remain at the bottom of the haul bag. It never even made it that far. Packing for the trip, the duo “forgot” the hammer and pins. Rowell found out on the fourth pitch, too late to do any good.

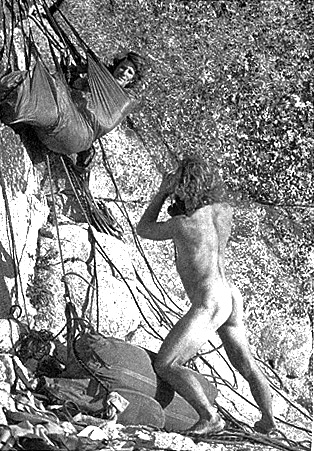

The trio climbed well together, and not without comic relief. Rowell recalls jumaring onto a ledge at dusk to find Robinson and Hennek, both naked, lounging at the belay, sucking on joints.

Though they were ensconced comfortably on the ledge, “Suddenly, Galen needed a hammock shot,” Robinson recalls. “Quick, c’mon, we can do this,” insisted the excitable Rowell, as he hung the hammock.

Enlarge

Robinson, nates bared to the Valley, took the photo of Rowell in the hammock. Unknown to Robinson, however, Hennek photographed him photographing Rowell. The photo was submitted with the rest to National Geographic, and made it to the final edit, fueling speculation that it would be the first photo of a naked Caucasian in the magazine’s history.

Back on the route the next day, Robinson asked for the Robbins Chimney, an unprotected 5.9 slot that even today most climbers avoid, preferring the 5.11c hand crack out left. “In those days, offwidths were at the frontier of free-climbing difficulty,” Robinson says. Eighty feet out, unable to protect the chimney clean, he squirmed his way toward the crux, contemplating the 160-footer onto a ledge if he blew it. “I felt like [that pitch] brought my whole offwidth career to a conclusion,” he now says.

Rowell also recalls Robinson’s artful lead on the Robbins Traverse, freeing moves most climbers would have aided. “He was ahead of his time, pushing his climbing like that on a Grade VI,” says Rowell.

In three days they scaled the wall without driving a single pin. Robinson got his climb, and Rowell got his story. When National Geographic hit the stands a year later, it featured a cover shot of Hennek. The story, “Climbing Half Dome the Hard Way,” seemed to find its way into the hands of every aspiring climber of the generation. The piece ushered in a new climbing zeitgeist. It also made the three climbers famous. Singled out as the idealistic and spiritual leader of the team, Robinson gained a reputation as a kind of Emerson of the climbing art.

“Doug’s always been a breath of fresh air,” says Rowell. “He has a sense of balance untainted by a search for personal glory. His credo has been to do well for himself and to enjoy the act of living for its own sale. It’s a lesson that today’s climbers should keep in mind.”

Many of today’s ego-driven climbers could indeed learn from Robinson. To him, climbing is a catalyst for self-discovery. “Mountaineering means just glad to be here,” he says. It’s not the frisson of climbing that captivates. “It’s the rhythm of the focusing quality,” he says in his 1988 video classic, Moving Over Stone. “Climbing can integrate body, mind and emotion,” Robinson adds. “That makes it a powerful meditation, A physical meditation.”

Robinson’s prose also flows from the heart. Its rawness grabs readers and nudges them into the mountains, where, according to Robinson, we would all be better off. Muir himself wrote that “the clearest way into the Universe is through a forest wilderness.” Robinson charges himself with keeping that wisdom alive.

“We all came out of a wild state, and we’ve drifted very far from that,” he says. “I like to see my residence in the 20th century as sort of an accident; I’ve tried not to live anchored to the general culture. The wilderness is a different kind of culture that can’t speak for itself, yet it has immense power to instruct. Through effort, time, quiet, attention, and humility, we can all hear its message.”

Robinson’s message is starkly apparent in his landmark essays, compiled in his new book, A Night On the Ground, A Day in the Open. It is plain as a Sierra storm in “Tuesday Morning on the Lyell Fork with Eliot’s Shadow,” a poetic essay about a whimsical ascent of Mount Lyell. It resounds in “The Climber as Visionary,” in which Robinson compares drug-induced super awareness to a kind of miracle of mindfulness he finds in running and climbing. The message also appears in “Camp 4,” a benediction of the community of climbers that thrived in the Valley’s Golden Age.

Perhaps the essay that best distills Robinson’s message in one joyous leap of faith is his treatise on movement, “Running Talus.” “Running” contains all the classic Robinson elements: action, contemplation, and instruction. “People don’t teach you to climb – the rock teaches you,” he writes. “You can simplify the learning process by going directly to the source.”

In “Running Talus,” Robinson advises us to hone our climbing skills by sprinting in talus, the jumble of boulders at the base of mountains. He struck on the idea after years of traversing the extensive fields talus of the Palisade Glacier. He hade a game of it, challenging himself to cross talus faster and faster, until he could run through it without stopping.

“What caught my attention is how well talus running actually worked. You could run through it and not get hurt as long as you were mindful of the present moment. You get the same kinesthetic freedom in talus running as you find in say, backcountry skiing. Little by little you approach the limitations of your nervous system; once you get it, it’s like the freedom of flight.”

“You’ve got to remember he wrote that essay at the tail end of rock climbing’s Golden Age,” says Dan Away, veteran Sierra climber and friend. “People were pretty heady at the time, talking of all the great routes they were doing in the Valley. Doug turned his back on that and hearkened to the primitive beginning climbing. It’s elegantly simple to think of starting a climbing career by running on rocks.”

Elegance found in simplicity seems to have instructed Robinson’s entire life. His mother, Helen, whom he credits for inspiring his writing, told him never to lose touch with the earth. She concedes her eldest may have taken the message a bit too far. He grew up in the Bay Area’s tony Los Altos Hills, son of a NASA aeronautical engineer. When he was 16, Robinson ripped his driver’s license to shreds because he detested mechanized travel. “We helped him glue the pieces back together later on when he decided he needed it,” recalls his father, 89-year0old Russ Robinson.

After graduating high school, Robinson moved into a tent on a nearby 4000-acre ranch. He shared the site with his climbing friend, John Fischer. They lived like dharma bums, subsisting on peanut butter and jam, talking climbing, and making plans. Robinson spent his days at Foothill College, often running the four miles between campsite and campus. Nights he studied and devoured the writings of Muir, Thoreau, Nietzsche. Ideas began to incubate into a way of coming at the world: voluntary poverty, taking pride in doing with less, turning his back on a money-obsessed society.

“We were lucky to come of age in a time of prosperity,” Robinson says. “Back in those days it was easy to live on the fringes of a fat culture.” The fringes included stints in Camp 4 and the Sierra’s Eastside, where he worked summers as a guide at the Palisade School of Mountaineering. There, in 1967, he met the 52-year-old Smoke Blanchard, a friend of Norman Clyde’s. “Smoke was a brilliant and ornery character,” says Robinson. “A mountain salt who had lived climbed, and guided in the Eastern Sierra for decades before the younger generation arrived.” In Smoke, Robinson found both mentor and kindred spirit. Smoke introduced Robinson to a jumble of high-desert granite boulders to the west of town: the Buttermilk. The Buttermilk became a haven to him, a place to think, write, and climb.

After completing an English degree in 1969, Robinson migrated to the Eastside for good. There he orchestrated a coming together that could only have occurred in the late ‘60s. First, Robinson convinced the owners of Cardinal Village, a collection of rough cabins usually open only for the fishing season, to allow him to stay through the winter. Then he pulled in Fischer, Fischer’s wife, Alex, and a mutual friend, Carl Dreisbach. Eventually they were joined by a hodge-podge of climbers, skiers, and various and sundry friends from the Haight, long-hairs all, remnants of the crash-pad-living, motorcycle-riding Armadillos. Fischer lost no time anointing the group the new incarnation of the Armadillos, and the party began.

Word of the “hippies up Bishop Creek” leaked out to the conservative burg of Bishop (still known as the Mule Capitol of the World), and before long, the friends were regularly visited by the county sheriff, who glassed the encampment from an adjoining road cut. Unabashed, they climbed, skied, drank, smoked, danced, dropped, screwed, and designed gear, and schemed how to avoid the war in Asia. As the winter of 1970 progressed, some well-known wanderers from other parts of the state showed up to join the fun. Chouinard was one of them. So was Rowell.

Through it all Robinson continued to guide, climb, write, and help others get into the mountains. One of those was an impressionable Bishop youth, Gordon Wiltsie.

“I was this dweeby, upstanding kid who was interested in climbing, and Doug took me under his wing, in his grandfatherly way,” says Wiltsie, now an accomplished outdoor writer and photojournalist. Robinson didn’t just teach; he gave his time freely.

“He really does care about mentoring people,” says Wiltsie. “He helped me find clients for my photography, and even volunteered to edit my first published piece of writing. He’s still turning up projects for me.”

Although Robinson says his ultimate goal as a teacher is to make himself superfluous, he believes in transferring wisdom from one generation to the next. This sense of duty was one of the reasons he was elected the first president of the American Mountain Guiding Association. “Experience is the best way to pass on teaching and judgment, which are the two most important factors of guiding in the mountains,” he says.

Robinson’s selflessness is perhaps a mixed blessing: although his kindness has made him a beloved figure, he admits to feeling ambivalent about his own worth. He’ll take the time to give his all to others, but often at his own expense. He’ll lose himself in he moment, but moments turn to hours, and hours to days.

“Time and Doug Robinson have nothing common,” says Wiltsie, echoing an observation made by most everyone. Robinson’s propensity for tardiness has become the stuff of legend. “Did you ever hear the story about when Doug and his parents were cleaning the Rock Creek cabin?” asks Kristen Jacobsen, Robinson’s wife of five years. “They decided it needed painting, and Doug volunteered to drive down to Bishop to buy the paint. He didn’t return for three days.” We laugh; it sounds like other Robinson stories I’ve heard.

And then there are the stories that don’t inspire laughter. “He was gone more than he was around,” recalls Claudia Axcell, to whom Robinson was married for less than a year, “and I wasn’t willing to accept that.”

Robinson’s prolonged absences were perhaps the downfall of at least two of his four failed marriages. He’s pained by those losses, but can’t explain why it took four defeats to learn the lesson. “It’s a mystery I’ll have to live with,” he says.

What is a mystery for Robinson folds in neatly with the paradigm of the boy who never grew up. It’s the key to his charms and quirks. But now that Robinson has Kristen, Tory, and a 10-month-old daughter, Kyra, he’s been forced to find a balance. “I’ve had my retirement, and now I’m at work,” he says.

His work includes teaching courses in guiding, climbing, and mountaineering at Foothill College; writing; and giving slideshows. And then there is his master work, a self-imposed dissertation called “The Alchemy of Action,” in which Robinson theorizes about a connection between extreme sports, noradrenaline, and naturally occurring visionary states. He’s worked for years to synthesize the theory into book form, and he says he can finally glimpse the end of the project.

Meanwhile, Robinson continues to find inspiration in things high and wild, and he isn’t really at home unless he’s within the folds of the mountains. “The first night back in the mountains, I’ll have city dreams, like being lost in a shopping center,” he says, shifting, looking out the window at the falling snow. “It takes about three nights to purge that stuff in order to slide into a different level of consciousness.”

And Robinson’s thoughts never stray too far from that altered state. He still sports a hit list of climbs: The Nose (he was stormed off a few years ago), and a 2000-foot ice climb “not far west of Whitney” he’s eyed for years.

When asked about his hopes for the next generation of Sierra climbers, Robinson chortles. “Mindfulness,” he says. ![]()